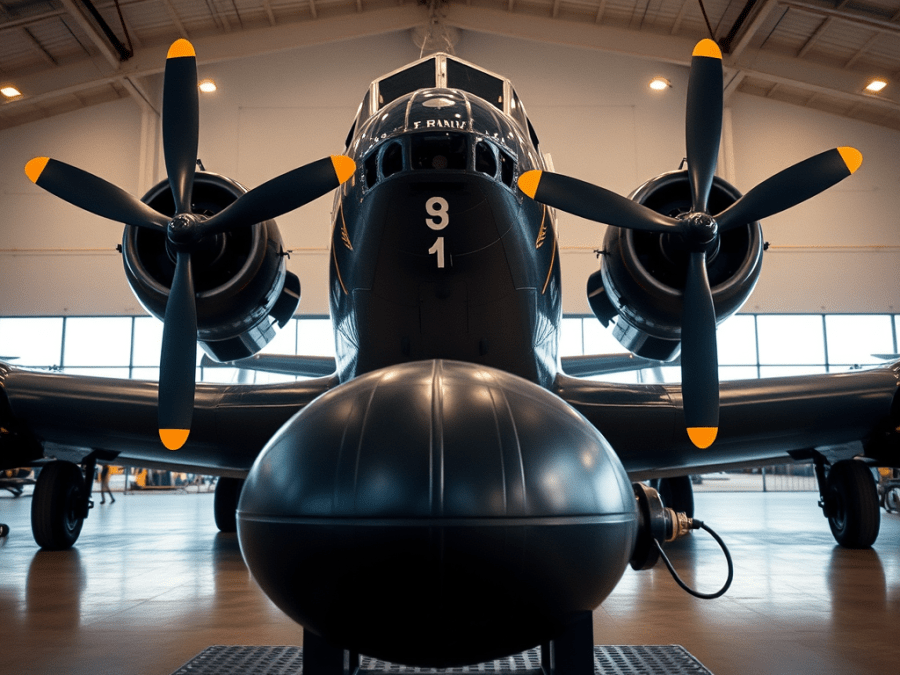

We went to The Bomber Command Museum in Nanton, Alberta May 13 2023 for the 80th anniversary of the Dambusters, these were some of the most famous and heroic missions performed by the Lancasters during WW II in Europe.

They started and ran 3 of the four Merlin engines, with one being down for prop work. It is quite an experience each time I’ve seen it. Also on display was a replica of the “bouncing bomb” used for these missions and replicas of various other bombs delivered by Lancasters including the 22,000 lb “Grand Slam” Bomb. All designed by Barnes Wallis.

To fundraise they were selling a special artifact. The 5 last remaining replica bombsites actually signed by the last surviving Dambuster Bombaimer, Sqn. Ldr. G.L. “Johnny” Johnson MBE DFM, now deceased. This is a primitive looking wooden Y-shaped device that was used handheld by the bombaimers to gauge distance to the dam during bombing runs.

Richard de Boer, who has been a guest speaker at our meetings previously, gave a fantastic presentation in the hangar to a large and very interested audience. His discussion covered the history of 617 squadron, the “Dambusters”, from the dam raids to the end of the war. Their accomplishments after the dam raids were equally remarkable, including special D-day operations, attacking and sinking of the battleship “Tirpitz”, high altitude bombing of hard targets like V-3 weapon facilities and many other operations. Richard always gives a tremendous presentation. Simply put, it was outstanding.

After the Lancaster was run, the Halifax Team took over and ran one of their Bristol Hercules, 14 cylinder radial engines for the crowd. The test run was incredible as the spokesperson Karl Kjarsgaard put it, “converting High octane fuel into noise”. It is loud! To watch this engine run is a spectacle, it is truly a “beast”. Apparently, in flight it throws a lot of oil back so the airframe aft of the engine would be covered black. Much credit to the team member running the throttle seated behind the engine wearing a half mask and goggles. It doesn’t get more manly than that! (See pic.)

I know many of you probably monitor your engine Cylinder Head Temps, from 2-6 cylinders. How do you monitor them on a 14 cylinder engine during a ground test run? These CHT’s were taken manually, while running the engine, with a handheld infrared heat gun, by a crewmember, that’s how!

The Bristol Hercules engine was designed by Roy Fedden, who was the engineer that designed most of Bristol Engine Company’s successful piston engine designs.

Karl said “the man was from mars” humorously referring to his incredible genius. Karl had a cut-away display of an actual cylinder/sleeve/piston combo so you could hand turn it to see it’s operation. The sleeve is the burning chamber and moves up and down and side to side to align with ports, 2 for intake and 2 for exhaust. It becomes a triple motion when the piston is added to the mix moving up and down. It is a work of mechanical perfection to see these parts working in concert. It becomes completely mind boggling to imagine 14 of these in operation per engine, times 4 engines. So, 56 cylinders per aircraft, rotating at up to 48 revolutions per second at take-off power. WOW!

Karl said “It runs like rubbish (he may have used a different word here, lol) at idle but nobody cares…it smooths out at higher Rpms. Engine run demos are about 1,800-1,900 rpm, Cruise is about 2,200 rpm and take-off is 2,900 rpm. I NEVER want to go to Take off power as some parts are virtually irreplaceable.

The Halifax is about the same the size as the Lancaster but with more Horsepower. It had up to 200 more HP per engine than a Merlin engine, so up to 800 more ponies per Halifax.

The Merlin engine was well matched to the “Lanc” airframe but when initially tried on the Halifax it underperformed. So, they thought we need a “Big Brute” of an engine to put on this aircraft, so halfway through the production line they started building the Halifax with the Hercules and it became a hot rod and tougher than nails.

In particular, the Halifax/Hercules Mark VII variant was fuel injected not carbureted. It was fast by bomber standards. It was often said that “the only Mark VII crewmember that could identify a Lancaster in the air was the Tail gunner.”

The Halifax – the most significant combat aircraft in Canadian aviation history?

We will have to discuss this next month in part 2 of this article. I was enjoying writing this so much that it ended up too long for one article, so I will publish the rest of the story in July, stay tuned.