Something that often strikes me about our airplanes is the wide array of technological contrasts they present. Airplanes have been around for well over a hundred years now, and aviation as a whole has undergone some unbelievable transformations in airframes, engine technology, and navigation advancements.

Some of that ever evolving technology has made its way into our corner of aviation populated by ultralights, homebuilts and small certified planes. As a result, we often find recreational airplanes sporting a real mix of technology, from seemingly ancient tractor-style mechanisms to the latest panel mounted electronics. It’s really interesting to me to see what’s changed, what hasn’t, and how it all fits together.

Lets start with engines. The Rotax line of two-stroke engines started out in snowmobiles back in the 1950s. Yet you can easily find these engines still plying the skies, as they have been since the 80s, in planes like Merlins, Kitfoxes, Chinooks and Beavers. But the Rotaxes now have some pretty cool tech built in. I really enjoy the contrast between the old dirt simple two-strokes designs and the more recent iterations that use modern and reliable dual electronic ignition and liquid cooling systems.

I don’t include the Rotax 912 series because I don’t consider them to be old technology. The 912s have been around since 1989 and have been under continuous development ever since. The basic design is pretty advanced, and later turbocharged models are really sophisticated.

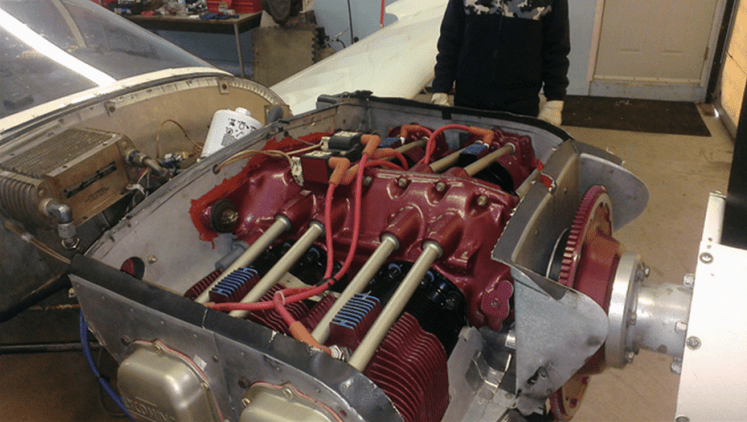

By contrast, Continental and Lycoming aircraft engines could easily be considered ancient. They started out in the 1930s powering small aircraft of the day, and were then widely used through World War II and beyond. Their carburetors and magneto ignitions could also be found on tractors, cars and trucks of that era. The engines have seen some minor updates, but they’re still largely as they’ve always been.

Nowadays, though, there’s quite a bit of contrasting technology that gets bolted on to these dinosaurs. Electronic ignition is the most obvious. Lightspeed, P-Mag, Surefly, and even Lycoming itself all produce modern, durable ignition systems strapped onto powerplants whose origins date from nearly a hundred years ago. Fuel injections systems also fit into this category with an excellent example being Calgary-based Simple Digital Systems (SDS).

Let’s not forget engine monitoring technology. Bob Kirkby’s 1964 Piper Cherokee, which is 61 years old at this writing, has a digital engine analyzer that can display and record a wide variety of engine operational data such that it can pinpoint the very second when any anomalies, such as plug fouling or valve issues, occur.

Note that none of the modern tech I’ve mentioned is particularly ‘new’ anymore. It’s been around for a number of years now, but what makes it important is that it’s largely accessible to guys like us. For instance, we no longer have to rely only on tractor-based carb or magneto technology for our engines.

Having said that, there are reasons that the old tech still flourishes. It works and it’s reliable. Its faults are well known, as are preventions and fixes. But the biggest reason we still have such old engine designs is how expensive it is to get ANYTHING changed or re-designed on certified airplanes, which is where most homebuilt tech derives from. That’s where our end of aviation really shines. We can experiment. We can take advantage of new thinking pretty cost effectively.

the assembly line.

Doug Eaglesham once owned by This Flight Designs CTSW advanced ultralight. Hailing from Germany, ittypifies European design efficiency. It’ll fly at 145 mph on only 100 hp and about 5 gallons an hour. It has a very advanced panel, but still has old tech analog instruments.

In terms of aerodynamics, Europe has led the way with dramatically more modern and efficient airframes, frequently made of composites like fiberglass and carbon fiber. I include gyros and trikes in this group. Their panels and interiors (or pod enclosures, as the case may be) are equally modern, and most have Rotax 912 derivatives pulling them along. Maybe they’re not really relevant in a discussion about contrasts, but they definitely demonstrate how even the simplest aviation technology can evolve. I very much appreciate those modern designs and how they wring such great performance out of the materials they use.

When ultralights were first a thing, back in the 80s, they were almost exclusively aluminum tubing and polyester sail cloth. Lazairs, Beavers, Challengers, and Bushmasters all had single-ignition Rotax two-strokes strapped to them harnessing lightweight strength to help guys get into the air. And it worked really well. There are still plenty of the designs from that era still flying and sporting some pretty sophisticated panels and Rotax engines. Several Rans models spring to mind.

How about aircraft covering? These days you can take an airframe made entirely of the most ancient building material, wood, and cover it with the most modern fabric technology. You might not even have to paint it, either.

Oratex offers pre-coloured fabric already treated with sealant and UV protection. It can be used on certified planes, too. Additionally, it’s no secret in our club that Carl Forman’s RV-9, a traditional aluminum semi-monocoque design, is covered in adhesive vinyl sheets. Who could have possibly imagined even 30 years ago that you could encase your whole plane in stickers?

The most prominent contrasts, of course, sit right in front of us on our instrument panels. The array of modern digital avionics available for our cockpits is simply staggering, as are their capabilities. This goes for ultralights, homebuilts and certified planes. Frankly, I love that.

My Cavalier’s panel has a mechanical tachometer (I swear it’s nearly as old as I am), a mechanical aneroid altimeter and a simple analog airspeed indicator. By contrast, just inches away is a digital EFIS screen that that displays in one small space everything and more that the old instruments tell me for a literal fraction of the weight, parts count and complexity.

There’s also a whiskey compass, technology that’s hundreds of years old, contrasted with the four separate GPS devices I use, which are all accurate to within a couple of metres. They’ll tell my heading, ground speed, altitude and more. Those GPS’s, while capable, aren’t even that sophisticated by current standards. My ADS-B sure is, though. It shows me where certain other airplanes are as if I had an on-board radar unit.

And I can tell my autopilot to talk to one of the GPS’s and then fly me to anywhere I want to be. Along the way I can make telephone calls, or even make dinner reservations over the internet from a few thousand feet up.

Consider this is all in an airplane that’s 42 years old, of a design that’s over 60 years old, that’s based on another design over 75 years old! It’s made of wood that likely grew for centuries, and is powered by WWII era engine technology. The technological timeline the Cav scales is both magical and amazing.

It’s been terrific watching the parade of technological advancements in recreational flying, and I love seeing how the tech just keeps marching forward. Nearly everything in my plane, and I suspect in yours, too, was at one time considered cutting edge, but is now well on it’s way to being old technology, if it’s not already.

Looking back from here, I guess that seems to be pretty standard in this age of contrasts.