The Cav’s wheels touched down nicely on runway 25 at High River. I rolled out to the end and taxied for the ramp to join my wingmen, Doug Eaglesham and Dennis Fox, of Three Hills, for a big trip southbound. We were flying our planes to San Diego to visit the USS Midway, an aircraft carrier made into a museum. Visiting the Midway was just an excuse, as if we needed one, to fly somewhere interesting and far away.

I’ve lost track of how long I’ve waited for the chance to fly to San Diego, so I was super excited to be embarking on the realization of that dream.

We left High River – Doug in his Flight Designs CTSW, Dennis in his Van’s RV8A, and me in my beloved Cavalier – for the hour-long flight to clear customs at Cut Bank, Montana.

From Cut Bank we flew to Helena, bypassing it to find a track through the mountains to Dillon, our next fuel stop. It was in Dillon that my starter solenoid died. Thus, Doug kindly offered to hand prop me, and we were on our way again.

We lit out southbound following Interstate 15 as it coursed through the valley. It eventually turned southeast along the easier, lower terrain toward the Idaho border, but since we were flying, I figured we weren’t exactly married to the highway. I suggested we take a bit of a shortcut near Dell along a gravel road leading up into a higher valley and a route that would save some time and distance on this leg to Twin Falls. My wingmen agreed and we were soon over a high valley floor that topped out over 6600 feet. Patches of snow still speckled the few cattle ranches and forest reserves below us.

The weather was encroaching now from the west, threatening us with some moderately sized cells trundling over the mountain peaks. I began to doubt the wisdom of my shortcut. We had a little bit of precipitation, that fell as snow at that altitude, before we popped out of the valley near a small place called Liddy Hot Springs.

We were at the northern edge of the Atomic City complex where the Idaho National Laboratories are located. It’s a series of nuclear research and production facilities not quite in the middle of nowhere, but not too far from it, either. We made sure to stay well outside the facilities’ boundaries displayed on our GPS’s.

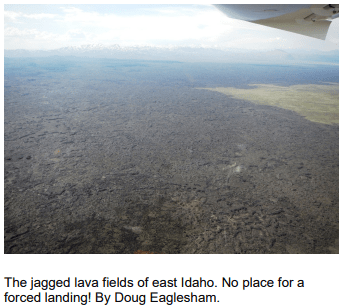

Soon we were above some of the most remarkable and scary terrain I’ve ever flown over; the massive lava fields of the Craters of the Moon National Preserve. This is a truly awesome area of ancient lava fields, old volcano calderas, and cinder cones. The region is still geologically active and scientists anticipate further eruptions there in the future. It kind of makes you wonder why they’d put nuclear facilities right beside it, though.

It was a visually stunning place, but we realized that to be forced down there would mean certain death from the jagged daggers of protruding lava rock. It was a frightening realization, and as spectacular as it was to witness, I was happy to have that region to our rudders.

Less than half an hour later we touched down at Twin Falls for our first night away.

Day 2

I was really looking forward to the day as we left Twin Falls on a pristine morning. Much the same as the previous day, this would one would have us over territory we’d never seen before, and I was excited about what lay ahead.

We passed the town of Jackpot, Nevada, directly on the border with Idaho, where a large hotel and casino sits right across the street from the town’s airport parking ramp. Convenient.

The nearly barren mountains of northern Nevada strode into view as we progressed southward, presenting a stark contrast to the Rockies we’re used to seeing. Alpine foliage is scarce there, as would be expected in such a dry, harsh environment. Nonetheless, the terrain was breathtaking.

We cut corners where we could and soon found ourselves tracking southwest paralleling I-80 across the northern reaches of the state. A seemingly endless array of mines passed beneath us, though what they produced we could only guess. There were pit mines and underground ones, some still active, some long forsaken.

At Battle Mountain we abandoned the highway, continuing straight on toward our first stop, Lovelock – Derby Field. Now we were over true desert; arid, sandy, and desolate beneath the sun’s relentless punishment. The flying had been smooth as glass all morning, but our approach into Derby was a rodeo ride as we bucked and fought with the thermals for the right to descend and land.

A derelict MiG-15 crouched in a corner of the ramp, a long-forgotten relic of a communist dream. Meanwhile, a steady stream of screaming, turbine-powered crop dusters taxied in and out every few minutes. We couldn’t tell if it was one or two planes making short hops, or several planes cycling one after the other.

Leaving Derby, we harnessed the thermals to lift us ever higher as we headed for Reno. NorCal approach vectored us right over Reno-Tahoe International, and warned us of a Southwest 737 departing right beneath us. We perched at 8500 feet, so the Boeing never presented a conflict, but it was cool to see it takeoff and climb right underneath us.

An inbound Piper Cherokee was our next concern as we passed into the Sierra Nevadas, but we spotted it ahead and well below us. No conflict.

Lake Tahoe glimmered off to the south as we flew over Truckee, just inside the California border. The upper reaches of the mountains were still thoroughly deep in snow and I couldn’t help thinking of the early settlers and explorers who dealt with the weather hardships those mountains regularly incur.

We sailed downhill from the Donner Pass toward Sacramento. All along the way I continued to be amazed at how the area was so familiar. It was because I’d ‘flown’ it on my desktop flight simulator several times. The fact that it allowed me to recall specific valleys and terrain features in the area speaks to how amazing – and useful – such technology has gotten.

Sacramento slid past off our right wings, diminishing in the haze as we arced southeastward skirting the western slopes of the Sierra Nevadas and pushing on toward Merced, our destination for the day.

We were perhaps forty miles north of Merced at 3500’ when Dennis called traffic at our eleven o’clock. I spotted a dark shape on the horizon that seemed about a mile and a half away and close to our altitude. At first, it seemed to be heading south at a speed similar to ours. Several seconds later I realized it was in fact heading northwest on a path about 70 degrees to ours.

It quickly took shape as a US Army Chinook helicopter, a massive dual rotor beast with an unmistakeable profile. And it was coming right at us. I called for our flight to descend a few hundred feet to create some space, which proved to be very prudent.

The Chinook loomed larger in the windscreen and several seconds later I passed right under it by a few hundred feet. I could see one of the helmeted crewmen in the half-open hatch just behind the cockpit, so I waved at him.

Doug reported that as soon as the Chinook overflew us it started climbing hard to a higher altitude. I reckon they should have done that earlier since they were tracking the west side of the compass.

We landed at Merced a few minutes later, tied down, secured a car, and went looking, unsuccessfully as it turned out, for a starter solenoid.

Day 3

The FBO manager at Merced was quite helpful in me locating a solenoid. In fact, I bought a whole, almost new starter. It had a cracked casting, but everything else on it was shiny and fine. I was able to haggle him down to a pretty respectable price and we were both happy with the out come. Doug and Dennis and I decided to wait until San Diego to effect repairs on the Cav.

We left Merced and turned southeast, our destination being El Cajon’s Gillespie Field, on the east end of San Diego. But as we progressed it looked doubtful we’d make it.

Fresno, and then Bakersfield passed by, and the further south we got the worse the distant weather appeared. We approached the south end of the San Joaquin Valley, which is delineated by the Tehachapi Mountains. The Tehachapi range runs southwest to northeast. We were high enough at Bakersfield to see over the southwest end of the range and what appeared to be a solid cloud deck beyond. There was no way to tell if it was an undercast, a broken, or a scattered layer until we got closer for a better look.

The northeast end of the range into the Antelope Valley was clear, as you’d expect, since it’s the gateway to the Mojave desert beyond.

We’d been aloft for more than ninety minutes, and weren’t sure we could make our intended stop of Chino due to the weather. We were also uncertain of the route beyond Chino, and we were getting hungry. We decided to divert and form a new plan for continuing.

We turned over the Tehachapi Range and made for Lancaster. Tehachapi itself is in a bowl atop the range and is famous for its soaring activity. Similar to the Crowsnest Pass in southern Alberta, it’s in a natural venturi where mountain waves slingshot sail planes well into the flight levels.

The wind grew steadily as we crossed the mountains and descended onto the right hand downwind for Lancaster’s runway 24. In the near and far distance we could see the storied Mojave Air and Space Port, and Edwards Air Force base, each of them cradles of so much aviation history.

Lancaster’s controller reported the wind as 250 at 14 gusting 26. It wasn’t much of a problem for landing, but it rocked our planes pretty hard as we fuelled. We each tied down snugly before heading to the airport restaurant.

We hatched a new plan over lunch as we checked maps and weather reports. We decided to skirt the USAF Palmdale plant control zone, then turn south into the Los Angeles basin near San Bernadino, and shoot the final hundred miles into Gillespie Field.

Doug departed first, with me and Dennis following. Our takeoff runs were pre-dictably short into such a headwind, and we turned southbound to stay west of Palmdale’s control zone, only a few miles south. A pair of new USAF Boeing KC-46 air refuelling tankers were flying circuits at Palmdale, which I thought that was pretty cool to see.

Doug`s impression, though, was that the tankers were unaware of us and that one was flying straight toward us. His reaction, naturally, was to change course and fly a different direction than what we briefed. Dennis and I lost sight of him against the urban sprawl of Palmdale proper.

Now we had a problem. We needed to rejoin with Doug over unfamiliar territory amidst moderate to severe turbulence. A fierce wind howled from the southwest storming over the San Gabriel Mountains a couple of miles to our right and creating moderate to severe lee wave turbulence and downdrafts. Dennis and I were near the top of the turbulent zone, but Doug was right down in the lee wave rotor. It was rough for us, but Doug was absolutely getting his teeth kicked in and was really struggling to climb out of it.

After fifteen violent and fruitless minutes of Doug, Dennis and I each describing ground features we were near or over, and Dennis and I trying to lay eyes on Doug’s CT, it was time for another plan.

We were rapidly approaching the Cajon Pass, where I-15 drains into the LA basin north of San Bernadino. Once south of there, we had to join up or Doug would have to fly separately through some of the busiest airspace anywhere. We really wanted to be together as a flight of three.

I spotted a large and easily seen warehouse complex in north San Bernadino. Dennis and I flew directly toward it and I asked Doug to do the same. I knew now that he was behind us, and I asked him to stay five hundred feet above our altitude and no lower.

Once over top of the warehouse, which Doug had now spotted, Dennis and I began a left-hand orbit around it. Before long Doug was doing the same thing and we continually updated each other with position reports. After two and a half orbits I spotted Doug on the other side of the circle going north.

“Contact!”, I radioed. “Okay, Doug, I’ve got you northbound at my ten o’clock for three quarters of a mile,” I reported. “Continue your orbit. Dennis and I are turning in now to join on you. Dennis, confirm you still have me in sight?”

“Roger that,” he replied as I banked hard toward Doug who was now turning into the north end of the orbit area.

As we carved around to join him, I asked Doug to roll out southbound, and I dropped in to his eight o’clock a couple of hundred feet away. I could hear the relief in his voice as he called me in sight. The old gang was back together again.

Now we just had to get through this airspace complex.

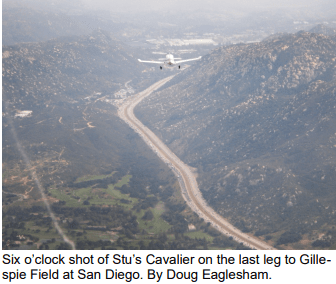

Dennis set up on my left side, and Doug stayed on my right as we switched over to SoCal Approach for flight following through to Gillespie. The next 45 minutes was some of the most intense flying I’ve ever done as we worked with one controller after another to get through the area.

We received a steady stream of vectors, altitudes changes, traffic alerts and at least a dozen frequency changes, before finally being handed over to Gillespie tower. Added to that was the typical reduced and hazy visibility of the marine layer that permeates the area. At one point I looked out a few miles ahead at a FedEx MD-11 at our altitude flying east to west. It was headed for Ontario airport, a major cargo hub in the region. There were only a few moments of relative quiet for us, and during one of them I looked out my right side to see Doug just off my wing snapping pictures, waving, and grinning broadly. It was funny as hell, and as unexpected as it was welcome.

We lined up in trail before switching to Gillespie tower. The controller was miffed that I didn’t have the ATIS, but I replied that I hadn’t had time and only had one radio. He vectored us to the right downwind for 27 right for spacing behind an inbound King Air.

We dutifully followed directions, but were shortly headed for some rapidly rising terrain.

“Gillespie tower, experimental Bravo Quebec Romeo,” I called. The King Air was going past us on final.

“Experimental Bravo Quebec Romeo, go ahead,” the controller replied.

“Tower, are we okay to turn base here before we smack into this mountain coming up?”

“Experimental Bravo Quebec Romeo flight, turn right base for runway 27 right.”

I cranked the Cav into a right turn, avoiding the mountain ahead, and the one to our right that now separated us from the airport. I felt quite familiar with the difficult terrain, even though I’d never flown here before. Well, not in real life. Once more my flight simulator proved to be a huge help in familiarizing myself with the area.

The tower cleared us to land and we were soon on a surprisingly steep final approach leg that I’d warned Doug and Dennis of earlier. Despite being ready for the approach, I was still surprised at how challenging it turned out to be. I had to fight hard to keep my speed down for landing.

We made our way to the transient parking and tied down. The nearby Enterprise car rental agency sent a man to pick us up just before they closed, and then we were on our way to find a hotel for the next few nights in San Diego.

Stay tuned Part two of this Adventure will be in next month’s Skywriter.