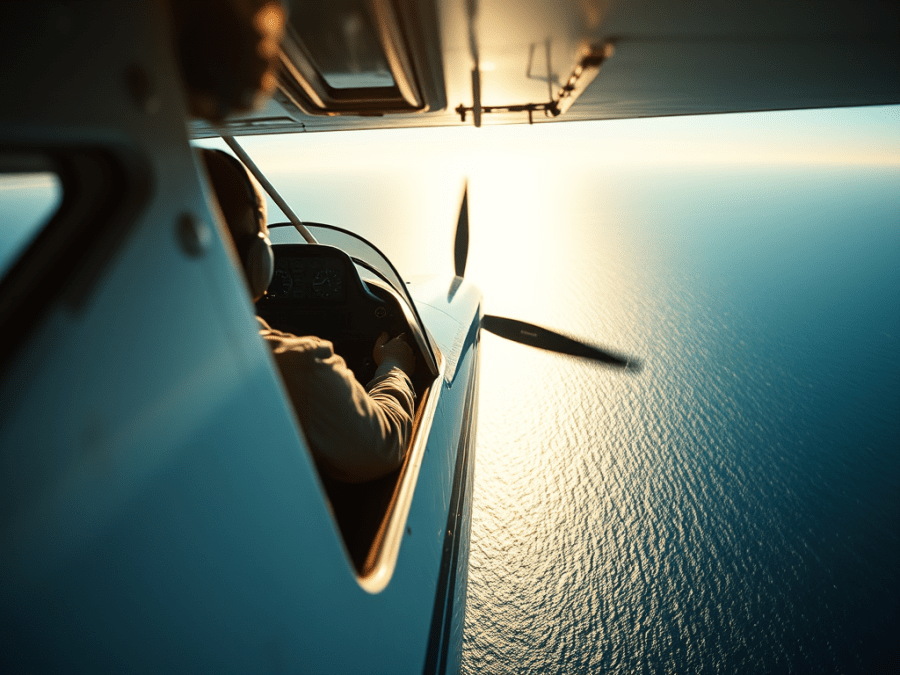

I looked down at the Strait of Georgia 8500 feet below and thought to myself that it didn’t look much like Oregon at all. Down there was deep, cold, unforgiving ocean. And there were eleven nautical miles between me and the next landfall. For all I knew (which clearly wasn’t much) it was teeming with vicious sock-eyed salmon, fierce man-eating halibut, and savage tuna fish. This whole thing was supposed to have been a trip to fly our planes to Oregon. So how did I wind up there, over the ocean, where I’m absolutely terrified to fly? Well, that’s actually a pretty good story.

It’s kind of Geoff Pritchard’s fault. He and I planned in late winter to make a spring flight to Oregon; he in his RV-8 and me in my Cavalier. Geoff, who loves old airplanes and cars, wanted to see the living museum at the Hood River airport. We also invited Gary Abel along with his RV-7. Gary wanted to see Vernonia, OR, where he did his RV transition training five years earlier. I just wanted to go on a flying adventure with my buddies.

A lengthy combination of unexpected events for Geoff, bad weather for everyone, and other unforeseen circumstances vaporized the Oregon plan and Geoff’s flying availability. Gary and I batted around some consolation destinations like Billings, MT, or Prince George, BC. We eventually settled on Spokane, WA. But a couple of days before departure he floated another idea, a long shot for sure because he knows well of my aviahydrophobia (that’s a term I just invented, by the way. It’s going into all the psychiatry books). Gary wanted to fly to Courtenay, BC. That’s on Vancouver Island. Islands are by definition surrounded by water. I hummed and hawed for several minutes. This would mean flying over actual ocean. My heart started beating a bit faster.

But instead of just saying no, I looked at a map, did some measuring, and plotted out a potential route to minimize time over the strait. I found one path that would give us only eleven nautical miles between islands. That’s about five minutes in the Cav. And if I was at 8500 feet that would mean I’d likely still be within gliding distance of something sticking out of the water that didn’t have fins. Even realizing that, though, my heart still didn’t slow down any. Phobias are seldom rational.

Courtenay is also adjacent to Comox. Gary, an air force brat, spent three of his teenage years there and often speaks fondly of his time and memories from then. I knew what it would mean for him to return there, especially in his own airplane.

But it would mean flying over water. Gary said he’d loan me a life vest for that leg.

There’ve been enough of my friends who’ve followed me on some pretty ambitious flying adventures. So, despite my well entrenched aviahydrophobia, I just couldn’t see any compelling reason to not reciprocate in this case. I checked the weather one more time, steeled myself, and told Gary I’d do it. But my heart was still racing.

Getting Gone

Gary and I both hangar at ChestermereKirkby Field east of Calgary. His RV-7 is the reddest thing I’ve ever seen. Not just the reddest airplane, the reddest anything, period. And it’s fast. He can easily hit 200 mph in level flight. My Cavalier’s normal cruise speed rests between 145 and 150 mph.

We launched from Kirkby’s about 9:00 a.m. on Mother’s Day and headed west to enter the Rocky Mountains via the Bow Valley Corridor. The wind at Kirkby’s shot from the north up to twenty knots, but it disappeared to near nothing once we got to the mountains. Sounds weird maybe, but it’s pretty common around here.

We were bound for Vernon, BC, where Pritchard lives and hangars. I was looking forward to seeing him again. He and I did some pretty adventurous flying together in the past and I was disappointed when he moved away from Calgary. It’d be good to see him again, if only for a short time.

Gary perched at 10,500 feet for the first leg while I cruised my way up to only 8500. I get headaches much above that altitude, but Gary has oxygen in his RV, so the altitude doesn’t bother him much. We coursed along the TransCanada Highway cutting corners where we could and taking in the mind-blowing scenery of the Rockies in the mid-spring sunshine.

Snow still deeply covered the middle and upper reaches of the stone ramparts along our path. I slipped through the Rogers Pass and enjoyed the heightened sense of speed that the more tightly spaced peaks offered. Once over Revelstoke and the Three Valley Gap, we turned directly southwest and downhill for Vernon. Gary was well ahead, and I heard his calls as he worked his way through the overhead and circuit. Then he announced a go-around, which surprised me. He’d miscalculated the steepness of the surrounding terrain and of the approach. Due to the thermals on final, and the heat erupting from the asphalt runway, he was too fast to safely touch down, so he wisely went around. He landed safely on his second shot.

Hearing his go-around helped me prepare for my landing and I paid more attention to my speed and height in the circuit, especially on final.

We drew a fair bit of attention at Vernon, especially from those interested in Gary’s plane. There are a lot of RV flyers at YVK, and his plane is an attention magnet, anyway. One fellow chatted with me as I refueled, telling me of another Cavalier that used to be on the field. It surprised him to learn it now occupies the hangar right behind mine at Kirkby Field.

Seeing Pritchard again was a treat, and we both wished he could join us. He offered us parking at his hangar, drove us for lunch and saw us off as we departed westbound for the coast. Taking off out of Vernon made me nervous. Using runway 23 put us right over Okanogan Lake and shoved my aviahydrophobia to full throttle. I tried to hug the southern shoreline as much as I could while climbing to a safe altitude to start westward. I was wearing the life vest Gary loaned me, which I admit helped ease my fears a little. When I reached 5500 feet, about 4400 feet above the water, I turned more toward the opposite shoreline and a valley that would allow me to gain height to cross the gentler slopes of the mountains enroute to Merritt.

Climbing was a bit tricky due to the altitude we needed, and the hot air affecting our engines. We occasionally eased off the power or dropped our noses, so we didn’t get too warm out front. The terrain between Vernon and Merritt was simply stunning to see. The area is normally quite arid and brown through the summer and fall, but today, in the midst of a relatively wet spring, the high plains shone brilliantly, beautifully green. I found it all remarkably similar to Wyoming.

At Douglas Lake I angled more southwesterly to intercept Highway 5, the well-known Coquihalla. Gary, on the other hand, was planning more of a straight shot from the Merritt area to the coast. He told me later that when he was over some of the more desolate territory of that route, he decided to head toward some populated areas to complete the leg to Courtenay. We were still in radio contact for most of that time. As for me, I turned south and followed the Coquihalla to Hope and the junction with the Fraser Valley. I could faintly see the coastal area the further south I flew and recognized the ever-present ocean haze that I’ve seen so often in other seaside regions.

As I rounded the corner into the Lower Mainland proper, I switched to Vancouver Centre and tried to get airtime for a radio call. After a couple of tries I finally got through, stated my intentions and received my squawk code.

I’ve always wanted to fly my own plane over the Lower Mainland of BC. As silly as my aviation fears and phobias may seem, so too might some of my goals and dreams. I’d tried to make a flight to the area a few times over the years, but it just never seemed to happen. It was happening then, though, so I was sure to take in all of it that I could.

The size of the sprawl was impressive. Urban areas mixed seamlessly with the rural ones, and I wondered which crops flourished in the fertile river delta. There were plenty of spots where creeping flood waters lapped at the land beyond the Fraser’s traditional banks. Vancouver loomed steadily from the mist, as did Sea Island where Vancouver International sits. The radio was incessant with traffic in the area, some of it going to YVR, some of it just passing through.

All too soon Vancouver Harbour and Stanley Park slipped past my left wing as I neared the invisible wall of my fear. My heartbeat faster once again. The good news was that as I gazed out ahead, the distances between bits of land didn’t look quite as daunting in real life as they did on the charts. I felt slightly more confident, but I still double checked the clasp on the life vest.

Vancouver sounded happy to be rid of me as they foisted me over to Comox terminal. The Comox controller was welcoming and happy to leave me at 8500 feet for as long as I needed, so I headed out over the water from atop Lasqueti Island.

I was more than nervous, I was scared. Not a panicky type of scared, just fearful thinking of the unthinkable. Well, that and the man-eating halibut waiting below.

A couple of minutes into the crossing I realized I was going to make it just fine. I looked ahead and knew I could glide to one shoreline or another from where I was. I instantly and significantly relaxed. I even smiled as I began my descent. Comox terminal switched me to tower who cleared me through their control zone to Courtenay. I was coming down now at about 700 to 1000 feet per minute. A few miles out I switched to Courtenay’s frequency and soon set the Cav down quite nicely on the smooth narrow runway. Gary and his winged siren waited patiently for me on the transient parking ramp.

The next day and a half were incredible. We didn’t have a car rented when we landed, but we met Charlie, a local RV-4 pilot who once flew CF-100 Canucks in the RCAF. He landed just behind me and kindly drove us the few blocks to our hotel. We spent the evening after supper walking the beach area around the airport and taking in the sights and smells of the oceanside location. People were out strolling and bike riding, enjoying their piece of paradise.

Courtenay celebrates and well uses its location by the sea. Gary played tour guide all the next day.

We talked our way into a rental car at the nearby Enterprise agency, whose manager treated us terrifically. Then Gary showed me around Comox and a few years of his childhood. We went to the school he attended, and explored the streets where he rode his bike, where his friends lived, and where he hitch-hiked around the area to jobs, play spots, and buddies’ houses.

We visited Kin Beach where his family lived in a tent for two months because no military or other housing was available. There’s a seesaw still there where Gary and a now-famous TV star each declared their dreams to one another; she was going to be an actress, she announced, and Gary affirmed he’d be a pilot. Missions accomplished.

He told of the airplanes and weapons stationed at Canadian Forces Base Comox; of how it was a frontline base for intercepting Russian bombers and launching anti-submarine airplanes. Back then, CF-101 Voodoos sat on their alert pads brazenly displaying nuclear missiles beneath their wings. Everyone knew the area would be a first strike target if the balloon went up.

With each location, each story, Gary slipped farther back into his past, a deluge of memories and experiences overtaking him and sparking long forgotten emotions of a growing young man. Some he merely glimpsed as they floated by, while others he grasped from the rushing torrent to spend more time with them. It’s plain they still mean much to him, as they should, and I’m privileged he shared the journey with me.

We grabbed some lunch and toured more of the island. We walked out to the incoming tide at Qualicum Beach, then drove to the other side of the island through Port Alberni and to Long Beach. The temperate rain forest was an astounding experience, and I couldn’t escape the parallels with Hawai’i, which I’ve visited several times.

Long Beach itself was fogged in to about an eighth of a mile visibility. We could hear the surf but couldn’t see it unless we walked a few hundred yards out from the forest edge. We could have easily landed our planes on the well packed sand. Long Beach was the farthest west I’ve been in North America, which I thought was pretty cool. Next stop, Asia, but the fog dashed any hope I had of seeing it from there.

We briefly stopped by the Sproat Lake Floatplane Base where live the two remaining Martin Mars flying boats. The base was closed on our arrival but the two Mars’, or what we could see of them across the fenced in ramp, were still impressive, especially sitting on their beaching gear.

Vancouver Island was an experience way beyond expectations. Of course, I’d heard about it and how people so enjoy being there. I’d just never given it much thought. Experiencing the place, though, opened my eyes to why it enjoys such popularity, and also why loggers and environmentalists fight over it. I wondered if the spruce that makes up my Cavalier’s structure might have come from the island’s thickly forested mountainsides.

Getting Back

We launched the next morning into another perfect day. Again, I kept the Cav close to shore as I climbed to 7500’ to head back east across the Strait of Georgia. But this time I wasn’t filled with as much fear. It was still there, but there was noticeably less of it. I wondered if I could get used to flying in this area if I did it regularly enough. Maybe, maybe not.

With his superior speed Gary was ahead of me as we backtracked along the published VFR route on the north side of the Fraser Valley. I listened on the terminal, then centre frequencies as Gary was given a new altitude to avoid incoming traffic. I wondered if I’d get similar instructions.

As I turned more northerly to pick up the Coquihalla the centre controller bid me farewell and instructed me to maintain VFR. I switched to 126.7 and announced my position a couple of times along the route. Getting no response, I tried to reach Gary on our inter-plane frequency of 123.45. No joy there, either, since Gary was likely already on Merritt’s frequency for his landing.

I switched back to 126.7 for a few more minutes, then about fifteen miles out of Merritt I also switched to the local frequency. I zoomed overhead still descending and saw Gary’s RV at the pumps. He pushed his plane clear of the fueling area just as I rolled up to the pump.

I fueled the Cav and met Gary inside the terminal to plot out our next move to Castlegar. We planned to spend the night there at my folks’ place.

We chose a route directly east back over Vernon, from where we’d follow a valley that joins Arrow Lake. It runs north and south in its valley and is actually a reservoir of the Columbia River. It curves to the east and joins the Kootenay River at Castlegar. YCG sits to the east side of a rather deep and steep valley at the confluence.

Our flight east proceeded without incident and we both again marvelled at the high, open terrain between Merritt and the Okanogan. We were soon atop Vernon and the soaring and practice area east of there. The mountains were steadily higher and more rugged with each eastbound mile. And the weather different, too. For the first time in the whole trip, we were seeing some clouds. Certainly nothing to worry about, but we noticed the change.

East of the practice area we curved around to a more southeasterly heading and picked up Arrow Lake. Gary chose to follow it all the way to Castlegar while I hopped over the valley’s eastern ridge for my descent into the Slocan, then Kootenay river valleys.

Gary’s radio calls to Castlegar got more muffled and static-filled as my descent put more solid rock between us. I rounded the corner into the Kootenay Valley and called Castlegar radio. The specialist warned me of two planes and a helicopter in the area, and I soon spotted my traffic below me in the opposite direction. The poor guy only had a 172, but he sounded happy enough with it.

Now I was free to descend. I used some S-turns to eat up the short distance left before needing to be at circuit height on the downwind left for runway 33. As usual, base leg had me headed straight into the side of a mountain a third of a mile away before I banked onto to the offset final approach leg. The runway, which has hosted 737s in the past, seemed enormous for such a small plane as the Cav.

We spent a great afternoon and evening with my folks, visiting and catching up on all manner of subjects. Gary, my dad and I, all had the same career, so there was never a lack of things to talk about.

The next morning was warm and well on the way to hot as Dad dropped us back at our planes. I gave the old guy (my dad, not my wingman) a hug, and Gary and I set about prepping our planes for the last leg to home.

We both fussed over our cylinder temperatures on climb-out, but we only needed to get from 1600 feet to 5500 before we could top the nearest mountain pass and start back eastward. This was easy mountain flying, basically following the Crowsnest Highway with several shortcuts thrown in. Ours was the route the road builders wished they could have made. But, alas, the Canadian Pacific Railroad ruled almost everything back in the day, and for better or worse cars and trucks now pretty much trace the routes of the iron horse, and likely will for eons to come. Too bad for them.

We had nothing but sunshine and a few tiny clouds hovering about, but none of them close to us. We might have occasionally had five or ten knots on the nose. The east end of the Crowsnest brought some changes, though, as the mid-day thermals shot skyward from the slowly greening prairie. The Livingston Range jumbled and bounced out my left window as I turned north for the final leg to Kirkby’s and home.

Near High River, YYC’s airspace rings cast their subtle warnings across my map so I nosed the Cav over slightly and started downhill. Less than 25 minutes later I banked hard over Kirkby’s to bleed off our excess speed for the downwind.

My approach was exquisite despite the gusty northeast crosswind. But just as I pulled power for a perfect touchdown, an errant zephyr caught the Cav right on the nose and we surged upwards a few feet. I quickly pushed the throttle, safely arrested the inevitable sudden plunge, but still thumped ignominiously to the grass. And Gary was there watching the whole thing.

Our sky journey to Vancouver Island offered up more than a few surprises, as any good flying adventure ought to do. My wonderful Cavalier once again flew me away to places I’ve never been before, and then safely back. I saw things I didn’t think I’d see, and I stared down one of my biggest fears, even if I didn’t completely conquer it. I feel I accomplished something. And now I can’t wait for the next flying adventure, for a time when reality once more travels beyond my expectations.