Our illustrious Editor Norm asked me to offer a comparison of the various types of aircraft I’ve been lucky enough to own over the years, in a couple of paragraphs. Although I consider myself a concise writer, I just can’t do it in only two paragraphs. I’ll weave some of my flying background into this to give you a better idea of why I chose the aircraft I did. I’ve built and flown two ultralights, bought and flown one homebuilt and two certified aircraft.

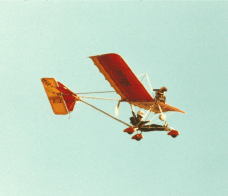

My first aircraft was a Mirage – a single open seat, tube and fabric machine with a Kawasaki 2-stroke engine producing about 40hp, if I remember correctly. I saw a picture of it in the Calgary Herald and just had to have one.

It wasn’t even an ultralight since the classification didn’t exist then. I think we called them Microlights. And there was no Utralight permit then so I was flying it without a license or permit, which was completely legal. Before flying it, I took 5 hours of dual training in a C150 then jumped into the Mirage and off I went. Life was simpler 1981. The Mirage was a ton of fun to fly, but as I later discovered all the aircraft, I’ve owned have been a ton of fun.

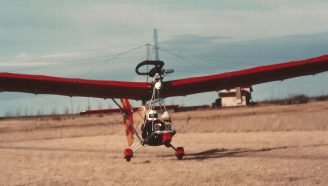

Bi planes always attracted me so when Darryl Murphy brought out the Renegade II in 1986, I immediately wanted one and bought one a year later. Once it was flying, which took about 10 months, I sold the Mirage and flew the Renegade until 2000.

Although I flew many long cross-country trips in the Renegade, include mountain trips, I wanted to do even longer flights, and also take passengers. So, in 1993 I took my PPL training and in 1994 purchased the Cherokee 235 (PA28-235). During my PPL training I flew C152, C172 and Cherokee 180 aircraft which left me with a preference for low rather than high winged aircraft plus I found the Cherokee more comfortable.

From that time on I’ve been a 2-airplane person. The Renegade served as a great around-the-patch, open-cockpit aircraft which I especially enjoyed flying early in the morning before going to work. The maintenance was easy to perform myself and inexpensive. The Cherokee 235 on the other hand is a fantastic cross-country aircraft offering exceptional comfort and very long legs of 5.5 hours plus reserve at 150 miles per hour. It carries 1300 lbs which easily accommodates 3-4 people, lots of baggage and full fuel. Two missions – two airplanes.

In 2000 I sold the Renegade and purchased a Starduster Too, a homebuilt aircraft.

I still wanted a biplane, but a little more performance was in order. This aircraft served the around-the-patch mission well but offered reasonable distance flying too. I spent many enjoyable hours in the Starduster flying with others in loose formation and on several air adventures. However, in 2006 I got a hankering for an old classic aircraft. I really like the Piper line, so I sold the Starduster Too and went shopping for a PA12. Finding a beauty in Columbus Ohio, I purchased it and flew it home.

The importation process was time consuming, but I did all the work myself, so it really wasn’t very expensive.

This brings me to today and I still have the PA12 for the around-the-patch mission and the PA28-235 for the cross-country mission. Both are certified aircraft.

I expect a big question on everyone’s mind is how do the operating costs compare? Before I comment on that let me say that each of these aircraft has sold for more than I paid for it and in the case of the two I now own their market value is more than I paid including an engine overhaul on the Cherokee and many upgrades on both. (The paint job on the Cherokee is over and above but that helps to maintain its value.)

Ultralights and homebuilts don’t generally appreciate in value as they change hands. I have always done all my own maintenance and on the certified aircraft I have a very good AME who works with me so that I can do most of the work. He inspects anything I do and does the annual inspections. Frankly the maintenance cost differences between the homebuilt and certified is very little except for the price of parts. Even then I shop around for certified parts and buy the best deals without having to pay an AMO’s markup. The addition price for certified parts can be accrued towards maintaining the overall value of the aircraft.

That being said, if you are the type who would drop your aircraft off at an AMO and pick it up when it’s ready you will most definitely pay a lot more for maintenance. This is no different than maintaining a car. By taking an active part in the maintenance, and more importantly the maintenance decision process, you will save big time. (See Mike Busch’s article in the September issue of EAA Sport Aviation magazine.)

Another significant operating expense is fuel. The bigger the engine the more fuel you will burn but the more performance you will get too. It’s not linear so you have to factor in the mission you are seeking. For example, over the years several people have asked me why I don’t build an RV10 to replace the Cherokee. The engine, load carrying and performance of both is very similar except the RV10 has a lot faster wing thereby flying more economically. However, I would have to spend twice the money and put in years building (I’m not fast like Troy). I want to fly now and spend that extra money on fuel to do so. It’s a trade-off. Many people don’t put enough thought into the desired mission when buying or building an aircraft. Start with that and then work backwards to find the most suitable aircraft for both the mission and you. I consider myself lucky to be able to have two aircraft in my hangar. But I also consider them to be investments. The extra care I take to keep them in prime shape ensures I will be able to sell them for at least as much as I put into them, less maintenance. Being able to use the right aircraft for the mission keeps the operating costs in line. Sorry for exceeding two paragraphs Norm, but the assigned mission required more fuel.

Bob Kirkby