WestJet Airlines’ Captain Wade Miller flies a Boeing 737 for a living. So, what would a guy like that do for fun? In Wade’s case, he flies an ultralight airplane.

I got to know Wade when he moved his airplane to Kirkby Field, just east of Calgary, a few years ago. Kirkby’s is where I hangar my own ultralight, a Merlin. We’ve been friends ever since and done quite a bit of flying together.

Speaking with Miller one day, the subject of simulator training came up. I told him I’d love to write an article about flying WestJet’s 737 simulator. He said he’d look into the possibility.

It took more than two years, but we finally managed to schedule a session in one of WestJet’s cockpit simulators.

Introductions

Miller is one of the most senior people at WestJet; Canada’s low-fare airline. Like the airline itself, Miller is based in Calgary. He has over 15,000 hours and sits at number 26 on WestJet’s pilot seniority list. He’s also a qualified 737 instructor pilot and most often delivers that instruction in a flight simulator.

Wade also flies recreational aircraft, most currently an ultralight registered Sonex. He’s owned a Cessna 140, an Aeronca Champ, and a Christavia homebuilt. It was in the Christavia that he joined me and my Merlin on a fantastic flight to Seattle, Washington, in the summer of 2009.

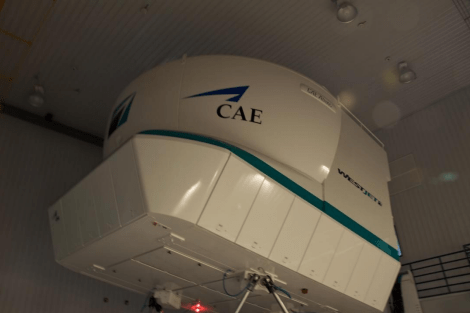

As agreed, I met up with Miller outside the WestJet hangar at YYC on a cold and snowy March evening. We entered the building and he showed me to one of three simulators that the airline owns. The sims, manufactured by CAE of Montreal, cost about 13 million dollars each. They’re all full-motion, Class D units, which means they’re so realistic pilots can actually log the time spent in them. In fact, when WestJet hires a new pilot, they do all their training in the simulator, and their first real flight in a WestJet 737 is also their first revenue flight carrying passengers on the line.

Let me describe the simulator. From the outside, it looks like a giant white-bodied spider. Long hydraulically-powered legs are anchored to a cement floor. Actually, it’s not really a floor. It’s a 30-foot wide, 8-foot deep, hexagonally-shaped concrete puck. It has to be that thick to absorb the forces from the full motion aspect of the sim. I hoped it would tolerate my landings.

Atop the legs sits a large capsule joined to an access walkway by a retreating bridge. WestJet’s logo adorns the capsule’s exterior.

Inside the sim capsule, there are chairs for a couple of observers and a computer workstation from which the instructor or examiner conducts the simulator training. Beyond the cockpit window is the visual display consisting of a large movie screen-like surface that wraps nearly 200 degrees from side to side. The visual simulation is to perfect scale from the crew seats.

Between the instructor’s station and the display screen, it’s all Boeing. The sim cockpit is absolutely identical to that of the real airplane; so much so, in fact, that should a part in a real 737 cockpit break, engineers can replace it with one from the sim.

Preparations

Before we got started in the sim, we went to a briefing room where the walls displayed the various cockpit panels and controls. Here, Miller explained some of the things we’d be doing and then he asked me what I’d like to do in the sim. My hope was to fly a few circuits at Calgary International. I’d been using Microsoft Flight Simulator X on my desktop computer to prepare for the ride, so I wanted to mimic my preparations as closely as possible.

Wade wanted to show off some of the capabilities of the 737 and the sim’s ability to copy them. He suggested we do one circuit on autopilot, and then I could choose what I wanted to do from there. I agreed, realizing it would give me some time to get used to the airplane and the speed at which things happen.

We moved to the sim capsule and I dropped into the left seat. Miller showed me how to adjust it. Then he hustled about between the instructor’s station and various panels in the cockpit and started switching on the magic. The cockpit steadily came to life as I strapped in.

An image appeared on the visual display screen of Vancouver International’s runway and Wade set about switching the view to Calgary. Suddenly, everything went dark on the display screen, though the cockpit stayed properly lit up. Wade made a phone call and said there’d be a ten-minute delay while an IT person fixed the error.

This was good for me as it allowed some more time to adjust radio frequencies and some other things, like the autopilot settings. I’m very impressed, though not very surprised, at how closely MS Flight Simulator mimics the real 737 cockpit. Everything before me was very familiar because of the time I’d spent practicing at home. That preparation really allowed me to start way ahead of zero.

Miller took several minutes to explain some of the aspects of the flight management computer, or FMC. Other than the guys and gals at the controls, the FMC is really the brains of the outfit. It controls, calculates, and displays thousands of parameters that affect the 737, like navigation and performance data. The FMC even tells what the airplane actually weighs at any given time on the ground or in the air.

With that all done, I looked out the front windscreen at the pitch black ahead and realized this is exactly how it must look for a WestJet crew over the ocean or a cloud deck at night. Miller confirmed my observation.

In fairly short order, the front view screen came back online, and with a flash we were suddenly staring at Calgary International’s Gate 49. Miller walked me through the various checklists required prior to pushback from the gate and then asked if I was ready.

Ready? I could hardly wait! I hoped I wasn’t drooling.

Then, we were moving, gently pushing back from the gate. The realism of the motion was simply amazing.

Wade started the engines on the push-back, beginning with number two on the right side. Once clear of the tug, we went through another checklist and then we were ready to taxi. At Miller’s urging, I pushed the thrust levers up to 40% to get us moving, then dropped them back down to idle once we were underway.

Ground steering on a 737 is accomplished with a small tiller wheel on the left side of the cockpit. I can affirm that it’s very sensitive. With Wade’s patient coaching, I taxied us to the hold short line for runway 16, where we completed another checklist. We entered the runway and I positioned us for takeoff. One more quick checklist and we were ready.

Gone Flying

Remembering Miller’s instruction, I pushed the thrust levers first to 40%, then after a two-steamboat count, up to 70%. We were rolling.

At 70% I punched two buttons on the thrust levers and the auto-throttles took over power control. The auto-throttles automatically adjust the engine power to what the FMC says is needed to launch the plane for the given weight, density altitude, field elevation, and a few hundred other parameters.

Of course, this was a jet, so at first, the engines responded slowly compared to what we’re used to with our piston aircraft engines. But once they got spooled up the acceleration was fantastic. The simulator mimics this effect by simply tilting the capsule nose up so the pilots feel more pressure on their backs. With the instruments and displays showing everything as it really happens, and with realistic engine noise and rumbling from the landing gear, the total effect was absolutely dazzling!

“80 knots,” called Wade. I looked at the airspeed indicator, but it was way beyond 80 now. Well past 100, in fact. I had some catching up to do.

“V1,” Miller called. Then, a second later, “Rotate.” I remembered this speed was supposed to be 132 knots.

Using both hands, I pulled back on the control yoke and was surprised at how much force it required. I set the pitch angle as closely as I could to 15 degrees nose up. The ground rumbling ceased.

“Positive rate,” Wade announced, referring to our rate of climb. “Gear up.” He reached over and moved the landing gear handle to the up position. I felt another steady rumbling, then a solid “thunk” as the simulated wheels tucked up into their simulated wells.

Wade reached up and clicked on the autopilot. I was both relieved and a little frustrated with myself. I was way behind the airplane, but I knew that I could catch up with just a bit more time. But this is how it’s done on the line; the airplane’s usually on autopilot for most of any flight.

Miller had warned me that flying the 737 requires a repetitive instrument scan pattern. I decided to concentrate on my instruments as he coached me in what to look for. It wasn’t long until we hit our target altitude of 7,000′. We continued southbound for a few miles, then fed the autopilot with a course change to 250 degrees.

Wade then fed in some light turbulence to add to the realism. We talked briefly about imagery on the sim’s visual display screen, which is taken from a relatively low-resolution version of Google Earth. It’s enhanced with things like computerized buildings at airports and in Calgary’s downtown core. All the correct geographic features are there, including the mountains on the western horizon. Wade got to wondering if Kirkby Field, the strip where we both hangar our own planes, would be visible.

We decided to go have a look since it’s right beneath the approach path for Calgary’s runway 28. We told the plane to turn right to a heading of 073 degrees, or due east. Wade switched off the autopilot and instructed me to hand-fly it. I kept us at 7,000′ (or as close to it as I could as I got the feel of the controls and trim system) and concentrated on managing the power to stay at 220 knots. Oddly enough, there are speed limits in the sky, like the limit of 250 knots below 10,000 feet. Approaching Kirkby’s, we both peered out the window and spotted the runways.

Suddenly, Miller announced, “I have control.”

“Roger,” I replied, “you have control.”

He took the yoke and reefed us into a hard right descending turn. I grabbed the steel handle above my side of the cockpit and held on. We were descending in an 85-degree bank for a nearly 360-degree rotation. I found myself so immersed in the experience I even looked over my shoulder to check for inbound traffic to Kirkby’s runway 34 as we crossed the runway’s extended centerline.

We leveled out a mile southwest of Kirkby’s a hundred feet off the deck at 280 knots, zooming across the field in a magnificent Boeing buzz job. I made sure to wave to us as we went by.

Landings

The buzz job complete, Wade turned the controls back over to me and had me climb back to 7,000′, or 3,500′ AGL for the Calgary area. I turned us back northwest bound to set up for an approach to Calgary’s runway 16.

Navigation was simple since I was flying in my own backyard. Also, the 737’s panel features a sophisticated map display showing navigation waypoints, NDBs, VORs, and the airplane’s actual and projected flight paths.

At the proper times, we deployed the flaps, the landing gear, and on occasion, the speed brakes. I turned to 190 degrees to intercept the localizer, overshot the runway centerline, and curved back in to intercept. I had a bit of trouble lining up with it, then realized I was too high. I tried thumbing the trim switch for nose down, and then took a look at the localizer again. I was too far left and paralleling it. Then I saw I was too high again. Way too high. I tried pushing the nose over some more and using more trim.

But by this time it was too late. I was on the centerline, but way too high to complete a safe approach. I said so to Miller, though in somewhat more vulgar terms, and he agreed. He immediately went to the instructor’s station and hit a button. Everything froze.

Wade pointed out that I was moving the trim switch in the wrong direction, which is why I was having such trouble with the altitude. I felt silly in my mistake, but Wade shrugged it off and set to work with the computer for a few seconds.

Suddenly, the display screen flashed and froze. Some instruments changed their readings and just like that, we were back on the approach at the right position on the ILS. Wade told me the airplane would fly the approach and I would take over for landing. Then he started us flying again.

The autopilot flew the approach perfectly down to about 400 feet where I took over.

I came in to the runway a little low and a few knots fast, but I touched down safely. I pulled the thrust levers to idle and activated reverse thrust. We lurched forward in our seats as the speed quickly bled off. I pushed out of reverse and moved to the brakes once we were below 60 knots. I was pretty pleased because had it been a real-world landing WestJet would have been able to use the airplane again afterward. I didn’t need all of that 8 feet of concrete beneath the sim just yet.

Miller returned to the instructor’s station again and reset us to the button of 16 for another go.

This time, I was nowhere near as far behind the plane as on the previous takeoff. I had a better understanding of what to look for and of what numbers needed to be where. I was surprised at how much attention the instruments demanded. For the last twenty-five years as a pilot, I’d flown with very few gauges and spent the vast majority of my time looking out the windows for flight information. Here, it was just the opposite. Nearly everything the 737 pilot does happens according to what’s on the instrument panel.

I asked Wade to set the radios so I could use Calgary’s VOR as a position reference. He told me that very few airliners use ground-based nav-aids anymore because of the proliferation of GPS. Still, it’s what I’d been using on FS X and it’d help me keep track of our position until I had a bit more experience with the map display. Miller happily obliged and I soon curved us around to final for 16 again.

Once more, I overshot the centerline, but managed to capture the localizer again quickly. With a much better feel for the combined trim and power usage, I flew the approach reasonably well, though a little low. Wade looked after the flaps and gear, and coached me on some of the finer points. I managed a reasonably good touchdown this time and was pretty sure I still hadn’t taxed the concrete beneath us.

With time for one more circuit, Wade reset us to the button of runway 16 once more and we were soon off. My skill was quickly growing and it showed on this takeoff. I only busted our altitude by a couple hundred feet. I turned us eastbound to bring us in on runway 28. Turning final over Kirkby Field, I made what turned out to be the best approach of the session. I had the ILS pretty well nailed, and the speed too. The trouble came at the touchdown. I slowed a little too early and didn’t have enough energy for a proper landing flare. The mains hit the runway hard, followed by the nose gear slamming down very shortly afterward.

I turned to Miller and asked, “Did we land, or did we get shot down?”

Wade laughed as I activated the reverse thrust and had us slowed to make the next to last available taxiway. Wade kindly informed me that the 737 is a very difficult airplane to land well with any consistency. I thanked him for that and appreciated a little bit better the reasons for that thick concrete beneath the sim.

What a terrific learning experience my WestJet 737 sim session was. I see now that WestJet’s pilots manage the 737 as much as they fly it. It’s a very complex – and capable – machine that demands deeply rooted skill and knowledge from its pilots.

I’m also deeply impressed with Miller’s mastery of the 737, and of his craft of flying it. He knows a lot more than just the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ of it. He also knows the ‘why’. In my experience, that’s always been the mark of a committed professional.

Thanks to WestJet and Capt. Wade Miller, I now have 1.3 hours of Boeing 737 time in my pilot’s logbook, and a flight I’ll never forget. Even though we never did leave the ground.