Recently, in an XAir, I was doing a soft field takeoff from a rough tufted-grass bumpy strip in the Philippines with a 10-knot crosswind rolling in over adjacent trees causing swirling gusts. After several false liftoffs, a sudden gust boosted the aircraft out of ground effect 12-15 feet high before I had the stick forward enough to pick up speed. The ‘copilot’ afterward reported that airspeed hovered a few mph above stall for nearly three seconds, too close ‘to the edge’. For situations such as these, you need to know not only the technique to use but you also need much practice to sharpen reaction times and to build instinctive correct reactions. The margins for error with short and soft takeoffs and landings can be small, and the unexpected can suddenly push the unprepared and unwary pilot ‘over the edge.’

These cautions are important because, in some situations, you can be getting out to ‘near the edge’ i.e., close to the limitations of the aircraft and the pilot. The uncertainties in the ground surface, the winds and gusts, and the peculiarities of your own aircraft can move the situation from ‘doable’ to trouble and even tragedy. So, you really do need to know what is possible here and to build experience in easier situations before attempting those that are more difficult.

I have some modest flying experience: six GA aircraft; a dozen ultralights; commercial and ultralight instructor ratings. Even so, for a recent set of flights to half a dozen short or soft ‘strips’, I made sure to do over 50 such practice takeoffs and landings in the prior days on a more than adequate grass field until I had brought my skills up sufficiently.

Here then are the techniques for short and soft field takeoffs and landings. When writing this, I was thinking particularly of an XAir tube-and-fabric aircraft (Standard model, tricycle, no flaps, Jabiru 2200A 85 hp engine). The principles given here, however, are basically applicable to any land aircraft, even tail draggers, though differences that may seem small can, in practice, be quite significant. STOL aircraft, for example, use unusually high-attitude, high-power approaches that provide some further complexities.

So, for any aircraft other than the XAir above, seek out more information and, at the least, consult the Pilot’s Manual for your aircraft. Best of all, take lessons with an experienced and knowledgeable flight instructor, preferably in the same type of aircraft.

Why Use Short or Soft Takeoffs and Landings?

A short field takeoff or landing is used when the available runway length is too short for normal takeoff or landing, or the obstacles in the flight path are too high for the normal techniques, or when both situations apply.

A soft field takeoff is used when the runway surface is such that the drag on the wheels would prevent the aircraft from reaching liftoff speed if normal techniques were used. This is the situation with soft earth, mud, sand, wet grass even if mown, long grass or weeds or bushes, or snow. A soft field takeoff is also used when the strip is so stony, bumpy, rutted, or potholed that it is imperative to reduce the load on the nose wheel as soon as speed builds up to prevent damage to the front wheel and strut. The soft field technique also reduces the load on the main wheels, so this is a plus in this same situation.

A soft field landing is used when the surface condition is the same as described for a soft field takeoff. In landing on soft earth, mud, sand, etc., the drag on the wheels brings the speed down quickly, but the accompanying deceleration unduly loads the front wheel and strut unless the soft field technique is used. If the surface is not truly soft or muddy or wet or snowy, etc., but just stony, bumpy, rutted, and so on, using a soft field landing technique can be used to similarly prevent damage to the nose wheel and strut.

How To Do Short and Soft Field Takeoffs and Landings

The following are the basic techniques for short and soft field takeoffs and landings. If there is a crosswind, then in addition apply the well-known crosswind control movements. Note, however, that these takeoffs and landings become much more difficult and problematic if the crosswind is significant, as the incident earlier related shows. It is common sense to not try them under these conditions and to go somewhere better if that is an option. If the aircraft has flaps, use these as appropriate to the maneuver (see your Pilot’s Handbook).

The Short Field Takeoff

Here is the technique for a short field takeoff. Position the aircraft as far back as possible to take advantage of all available distance; hold brakes then move throttle smoothly to full power; check gauges for full revs, etc.; release the brakes: move the stick back modestly as roll begins to ease load on the nose wheel; as soon as wheels leave the ground, move the stick forward sufficiently so the aircraft flies in ground effect (wheels about a foot off the ground) to accelerate; at best angle airspeed bring the stick back smoothly so the aircraft climbs at best angle; transition to normal climb speed when clear of obstacles.

The Short Field Landing

For short field landings, use a powered final and short final using the appropriate speed (see Pilot Handbook). When there are obstacles e.g., trees, fences, or power lines near the ‘threshold’ of the strip, you want the steepest final approach available; hence use flaps if you have them as well as the slowest appropriate airspeed; if there are no obstacles you still want this steep approach for the slower airspeed that goes with it, to reduce the ground run; set up this approach early and trim for the airspeed; don’t be afraid to use power to stay on the approach path as it is power that ‘controls your altitude’; you are trimmed for the desired airspeed so you do not want to alter this by significant movement of the elevator (gusts may necessitate such elevator movements, but these are temporary); because of the short distance available, you want to touch down soon after the ‘threshold’ so you have set up the approach path for this; flare and touch down; just before the wheels touch, ease back on the power, then as soon as the wheels are down use hard braking with the stick as far back as will keep the nose wheel almost off the ground. Too much stick back will unload the main wheels and deteriorate the braking, and worse, may also lift you back into the air. If the aircraft has flaps, bring them up after touchdown to increase weight on main wheels and allow stronger braking. If a crosswind exists, the nose wheel may need some more weight for directional stability as the aircraft slows and the rudder loses its effectiveness.

The Soft Field Takeoff

For the soft field takeoff, the aircraft shouldn’t be allowed to stop once you start taxiing (hopefully off a more solid area); at the start of taxi bring the stick right full back and hold it there; keep the aircraft rolling through the turn onto the ‘threshold’, bringing up the power near the end of the turn; desirably you quickly glance at the gauges to check for full revs, etc. (you are probably too focused elsewhere for this, so a copilot or trained passenger calling ‘All OK’ is good to have); the stick remains full back while ground speed increases, but as soon as the nose wheel lifts off, bring the stick smoothly forward so as to fly in ground effect a foot or so off the surface; let the aircraft accelerate to normal climb speed and continue to climb as usual. Sounds basically simple but getting it all sequenced and synced properly requires a great deal of practice.

Here are some ‘gotchas’ to watch out for:

- false liftoffs (watch for these in short field takeoffs too) where a gust or a bump puts the aircraft momentarily off the ground, but it isn’t ready to fly yet (airspeed too low).

- not moving the stick quickly enough forward after you have true liftoff so the aircraft climbs up too far (ground effect drops off quickly over a height of approximately half the wingspan) and the aircraft can sink back down and hit hard or bounce or even porpoise.

- moving the stick not far enough forward or too far forward just after liftoff (climbs too slow too high in first situation and descends back to earth in second situation, neither what you need).

- gusts adding or subtracting momentary lift in the critical liftoff, ground effect and initial climb phases.

The Soft Field Landing

Now here is the technique for the soft field landing. Up to the touchdown, it is basically the same as for the short field landing. At touchdown, you want the aircraft to alight gently with its weight coming onto the surface gradually, so the stick comes back to keep the nose wheel off the surface and the weight light on the main wheels, and then continues all the way back as quickly as possible (without lifting off again) to get the maximum attitude you can. Braking also begins at touchdown; generally, it is best to not quite lock the brakes. With wet snow or mud on the surface, for example, locking the brakes could just cause hydroplaning. On soft sand, however, locking the brakes might “dig the wheels in,” whereas keeping the wheels rolling may have much less braking effect (but more progressive deceleration). The stick is kept back as the aircraft slows and the nose wheel finally touches down.

Note that it is not good practice to ground the tailskid in the soft field landing or the soft field takeoff because of possible damage and even pitching oscillations. Also, in the soft field takeoff, it increases drag which you don’t want. With the XAir, I think a tail strike is possible under the right conditions of weight and balance, although I have not had it happen so far. I know it is possible with a Cessna 172, as I did do this once in my student days, much to the disapproval of the flight instructor.

Here are some ‘gotchas’ with soft field landings:

- don’t wait until the aircraft stops before easing the nose wheel to the ground (as the aircraft comes to a quick final stop the nose wheel can come down hard if you wait until then).

- if there is a crosswind, the nose wheel needs to come down earlier for directional stability as the aircraft slows and rudder effectiveness is lost

- if the aircraft has flaps, leave these down after landing to continue the extra lift (and the drag) they provide.

In a soft field approach to the strip in the Philippines mentioned earlier, liberal and continuous power variations were needed to keep the squirrelly approach in the gusty crosswind within bounds. For the XAir, a mean airspeed of 55 mph was used, this being 50 plus 5 for the gusts. If it had been calm, an airspeed of nearer 50 mph would have been used since the field was also short, so minimum roll was desired. At this strip, there was no go-around possible in short final because of trees at the far end, so you had to be sure you were on the right approach path early and then stay on it.

Aborting Takeoffs

For all types of takeoff, the abort point on the strip should be halfway down the available distance. If two-thirds of liftoff speed has not been reached by then, it is best to abort. Pacing off the available distance beforehand and putting a marker at the abort point can be a very good idea.

With Practice …

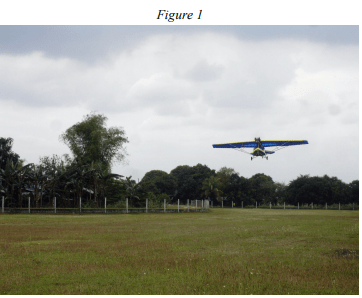

The first photo shows the XAir just about to touch down for a short/soft field landing over trees during practice at a more than adequate grass field. The trees dictated a short field approach; hence the slowest appropriate speed, about 50 mph, allowing for the light crosswind and gusts. If it had been calm, the approach speed could have been taken down to even 45 mph. The grass was not draggy enough to require a soft field landing, but it was done like this for practice. The distance from the white mark in the foreground to the back fence and trees is about 85 meters (about 280 feet), and the aircraft was stopped within this distance.

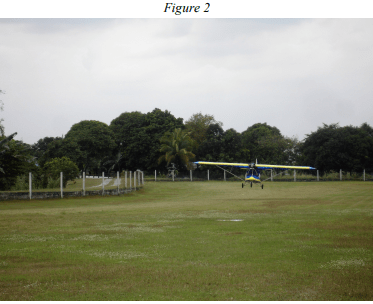

The second photo shows the XAir climbing out from a soft field practice takeoff at the same field. As can be seen, the aircraft is already climbing out by the 85-meter mark.

References

An excellent reference to these techniques is “Mountain Flying Bible – Revised” by Sparky Imesen, Aurora Publications, Wyoming, 1998.

[Doug Norrie lives in Calgary, Alberta, where he is currently building a Savannah STOL all-metal aircraft. He also flies in the Philippines, where he shares an XAir.]