Well, another eventful month is behind us. A lot of folks have been taking advantage of the Chinook-like weather we experienced in late February and early March. Personally, I’ve been flying nearly every weekend, and I’ve heard a lot of other members committing aviation on the radio.

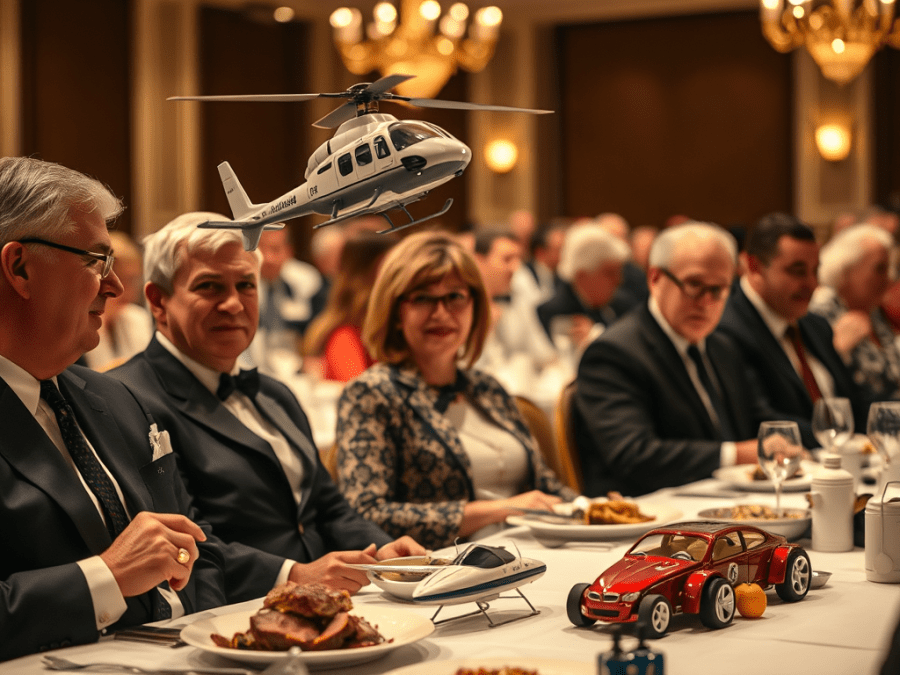

Of course, the highlight of the past month’s events has to be the Annual CUFC Banquet and Auction. Attendance was a bit lower than previous years, but still around the 60 mark. As usual, the catering staff provided us with a wonderful buffet dinner of roast beef and all the fixins.

Bidding was brisk on the silent auction items, but the real challenge for those attending was rescuing the boat and car from imminent doom with a remote-controlled helicopter. I know we had a winner, but I was laughing too hard to notice.

The live auction was thoroughly entertaining with the help of Barb Forman and Louise Kirkby, aka Vanna White. In all, we raised approximately $850 for the COPA Emergency Action Fund.

School is progressing quite well, and I picked up a little tidbit that I’d like to pass along. One of the discussions we had recently was around carburetor ice. I had always assumed that there was essentially only one type of carburetor ice and that it forms at the narrowest point of the carburetor in the venturi. However, there are three distinct types of carburetor icing.

The traditional icing found in the venturi is called fuel vaporization icing. It’s formed by a temperature drop created both by the venturi effect (higher airspeed forms lower pressure and lower temperature) plus the vaporization of the fuel as it passes from a liquid to a gas. This will generally reduce the airflow and enrich the fuel/air mixture, leading to rough running.

In addition to fuel vaporization ice, there is also impact ice. In this case, ice forms on the air filter and in the air intake to the carburetor. This leads to a general power reduction and can eventually lead to engine failure. Fortunately, this doesn’t affect VFR pilots too much as it generally requires snow or freezing precipitation to form. Carburetor heat is effective in overcoming this situation as it will allow air to bypass the frozen section and come in through the carburetor heat air intake. However, carburetor heat will not generally remove this ice once it forms.

The last type of carburetor ice is one that can affect us. Throttle ice is formed in the same way as fuel vaporization ice, but it forms between the throttle valve or butterfly and the wall of the carburetor at or near idle settings. This can form rapidly due to the large drop in temperature through the throttle valve at this point. Also, when the engine is at or near idle, the main fuel jet does not provide fuel to run the engine. Instead, the idle ports take over. These are a series of 3-4 small holes in the wall of the carburetor near where the throttle valve closes. What this means is that a very small amount of throttle ice will both seal off the idle ports and the air flowing past the throttle valve.

Most of us have been trained to avoid throttle even though we may not have realized what, exactly, we were doing. Most of my instructors always preached using carburetor heat on approach or descent when the throttle was pulled back to prevent carburetor icing. At this point in the flight, we are generally protecting against throttle ice as opposed to the more classic fuel vaporization ice… Who knew!