Last year I bought a 1947 Piper PA-12 (The Supercruiser) in the US and flew it home. While that sounds pretty easy, it wasn’t. But this story isn’t about what I went through to import the aircraft; it’s about the trip itself.

I should, however, tell you a bit about the lead-up to the trip. I had been thinking about an old Piper for a long time, and after selling the Starduster Too, I started shopping seriously. At first, I looked at all the models prior to 1950, but soon zeroed in on the PA-11 or PA-12. I wanted a Cub-like aircraft but with a little more performance and passenger-carrying capability than the J3.

It didn’t take long to cover the market in Canada and the US. I only found a couple of PA-11s for sale, but I found about 10 PA-12s. I started making phone calls, asking questions, and requesting photos. I found several PA-12s that had recently been restored and upgraded with O-320s, flaps, and more. Not only were these priced way too high, but I really wanted something that was more stock but rebuilt not too long ago.

I found three PA-12s in the US that looked like possibilities and spoke at length to the sellers and collected more photos. One jumped right out of the photos and grabbed my attention. If the photos and information were correct, this would be a great buy, so I decided to go check it out first. It was in Columbus, Ohio.

I had a feeling that if this aircraft turned out to be what it looked like, I would buy it on the spot. So I figured I better make some preliminary inquiries into the importing process before heading south. Transport Canada has downloaded this work to private businesses, so I looked on the Transport Canada website for the list of Minister’s Designees in Calgary. I was surprised to see there were a lot, but one in particular was recommended to me by my AME, so I gave him a call. We got together, and he (Allan) briefed me on the process.

Essentially, there are three ways to get an aircraft into Canada from the US.

- If you can take it apart, you can trailer it here and start the importing process after it arrives.

- You can keep it registered in the US and have a pilot with a US license fly it here (maybe the seller or a ferry pilot), or you can fly it yourself if you have a US license. Then start the importing process when it gets here.

- You can complete the purchase transaction in the US, deregister it there, and put a Provisional Canadian Registration on it for the purpose of the ferry flight home. This is the only way you can fly it back to Canada if you only have a Canadian license.

At first blush it sounded like the third option was straightforward enough, and I chose that method if I should buy this aircraft. Allan told me what paperwork to look for in the logs and files and what I should copy and bring back for him to look over.

So in early August, I flew to Columbus to check out this PA-12.

The aircraft was being sold by a broker because the owner, a lawyer, had recently encountered some serious family medical issues and decided it would be a long time before he had time to fly it. He wanted to sell but had no time to deal with it. The broker met me on arrival, and we drove out to the small reliever airport where the PA-12 was housed. All along, I thought the photos and data on the aircraft were too good to be true, so I was prepared for a big letdown. But when the hangar doors opened, I just couldn’t get the grin off my face.

I spent several hours going over the aircraft looking for faults but found none. Unfortunately, it was raining with a low overcast, so I didn’t get a demo flight. But that didn’t matter. The engine ran nicely on the ground, and it was only 10 hours since its annual. After dark, we went back to the broker’s office where I studied the log books closely, making lots of notes and photocopies.

By the time I hit the hay in the hotel that night, I had made up my mind to buy it. However, I headed home the next day armed with lots of photos, photocopies of pages from the logs, and many notes to review with Allan. The idea was for Allan to confirm that there weren’t any great obstacles to importing the aircraft before I proceeded to make an offer. This he did, and a couple of days later, I purchased the aircraft via phone calls and emails; and a cheque, of course.

It was built in 1947 and had a total time of 1650 hours with 620 since a complete restoration, including an engine and prop overhaul. It was in immaculate condition, and of all those that I found for sale, it was the second cheapest. I was more than pleased with my purchase.

The owner was not in a position to fly it to Canada, so I continued with my plan to fly it home myself. This required having him de-register it in the US, and I had to obtain a Provisional Certificate of Registration to fly it home; basically a ferry permit. Prior to this, I reserved the registration letters and was pleased that Transport gave me a CF-series because the aircraft was built prior to 1957.

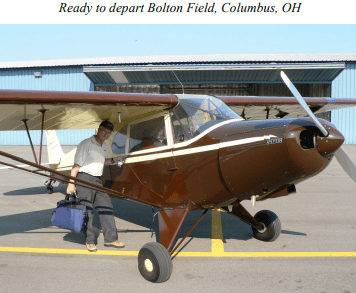

So I made plans to head back to Columbus on Thursday after the September long weekend. Early the next morning, I headed out to Bolton Field with the broker to claim my prize. I met the owner for the first time, and after some discussion, he had to leave for a “lawyer” meeting. The broker helped me get the PA-12 ready for the longest cross-country flight of its career. We stuck on the vinyl registration letters and the sheets of sticky vinyl I brought to cover up the American registration. We packed it full of logs and manuals, the wheel pants which were not installed, and my gear. Although it wasn’t very much weight, it took up the entire double back seat.

Finally, I filled the tanks with 38 gallons of avgas and filed a flight plan for my first leg. After saying my goodbyes, I fired up and taxied around the ramp a bit to familiarize myself with the cockpit and ground handling. By the time the engine was up to temp, I was ready to go.

I called ground control for taxi clearance announcing, “This is PA-12 Canadian Foxtrot Juliet X-ray Victor,” and I imagined what the controller was thinking. I’m sure he could see me from the tower and was probably wondering how it got to be a Canadian aircraft overnight. Anyway, he didn’t ask any questions, and I didn’t volunteer any answers.

It was a short taxi to the runway, and I was cleared for takeoff behind a 172 doing a touch and go. The day was perfect with a light wind down the runway and a clear sky. Takeoff seemed to take about 500 or 600 feet, and the rest was an elevator ride. I was amazed at how fast the PA-12 seemed to climb with very little angle of attack. I soon turned westward and settled on course for my first leg. Yes, I had my GPS along, strapped to my knee.

My first leg was 224 miles, which took 2.6 hours with a headwind. The headwind was to get gradually stronger as I flew west. My first stop was a small country airport called Jasper County, Indiana, about 40 miles south of Lake Michigan. As I approached, I listened to the airport conditions on their ASOS (even small airports have these in the US) and joined the downwind for 18 “on the 45,” as they say. Then an amazing thing happened.

Just as I turned base, I heard a pilot announce crossing the airport in a Stearman to join the downwind. I thought this was neat. Then as I turned final, I heard another identical announcement, but from another Stearman. Halfway down final, I heard it again (I had chosen to do a long final since this was my first landing in the PA-12). I was trying not to get distracted, but I had to take a quick look around, and I spotted three Stearmans in the circuit. I thought to myself, “Gees, this must be a time machine. I feel like this is 1947, and I’m surrounded by 1930’s vintage aircraft.” It was quite exhilarating.

In spite of the distractions, I made a good landing and taxied over to the pumps. By the time I got out of the aircraft, the first Stearman was taxiing in. I soon had all three parked on the ramp around the PA-12 (see photo). What a sight! It turns out the Stearman owners were on their way home from a Stearman convention and chose the same fuel stop I did.

I could have stood around for hours watching these beautiful machines, but I had a flight plan and needed to get going. With full tanks, two granola bars, and some water, I departed 1947 for my next stop. Next stop was Dubuque, Iowa, 207 miles and 2.2 hours away. Now that I was around Chicago, I turned a little more northwestward. The weather was perfect, and the airplane was flying great, so I relaxed and took in the pretty mid-west farm landscape.

My plan was to fly a great circle line northwest through Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Montana to Lethbridge, where I would clear customs. Then it would be a short hop to home base.

This leg took me across Illinois and into Iowa whose border is defined by the mighty Mississippi River. This was the 10th time I’ve flown across it in a light aircraft. Every time I do, I marvel at the long trains of barges floating cargo up and down the river. The size of the river and these barge trains can only be appreciated from the air.

My stop in Dubuque was only long enough to fuel up and update my flight plan. Then I was off on my next and final leg of the day. I would stop in Austin, Minnesota for the night, which was a short 141 miles. However, the headwind had increased significantly by now, and it took 1.8 hours to get to Austin. The ride was smooth until I started my descent when it got gusty, and I discovered the wind was about 15 knots and about 30 degrees from the right of Austin’s single runway. This presented me with my first crosswind landing challenge in the PA-12. I found the ailerons and rudder to be very effective and responsive, which was good in those gusty conditions. The landing wasn’t the prettiest, but it worked out okay.

I had used Austin as an overnight stop several years ago on a trip to Indianapolis. At that time, it was pretty run down, so I was pleased to see that a new terminal building had been constructed since I was last there. I tied the PA-12 down on the ramp, closed my flight plan, and found someone in the terminal who loaned me a courtesy car to drive into town and find a motel. For this, I was thankful since I was exhausted after a very long day.

I was up early the next morning only to look out at a low ceiling and drizzle. Naturally, this was not in the forecast from the night before. Oh well, when I hit bad weather on cross-country flights, I always look for the bright side. This morning that meant a leisurely breakfast, getting on the internet and studying the weather forecast, then driving back to the airport after stopping at a grocery store to pick up some cleaner and sponges so I could get the bugs off the wings.

At the terminal building, I studied the weather some more. A system had moved up from the southwest during the night, which resulted in 600-foot ceilings and drizzle around Austin. I was frustrated by the fact it only extended another 20 miles north. The forecast was for a slight improvement in the local area around noon, but it would worsen later in the day. The system was blocking my planned route northwestward and forecast to get worse that way until the next day.

While I waited, I took out my charts and planned a new route north from Austin, passing west of Minneapolis to Chandler, MN. This would get me away from the crud, and then I could head west into North Dakota.

Around 12:00, a pilot arrived IFR in a Piper Saratoga. He reported a ceiling of 600-800 feet but good visibility under the ceiling. I was tempted to go but decided to wait a little longer since I’m not too comfortable flying around so low in unfamiliar territory full of cell towers.

Finally, about 2:30, the AWOS was reporting a ceiling of 1000 feet and visibility of 6+ miles. I filed for Chandler and was in the air 25 minutes later. The ceiling was very ragged and probably averaged 1000 feet with low-hanging clouds scattered around. When I contacted the nearest FSS to activate my flight plan, the specialist said I could expect to be out of the scud in 15 to 20 miles. I flew with my eyes out of the cockpit full time, dodged a few low-hanging clouds, and missed all the towers. At 10 miles out, it was breaking up, and at 20 miles, I was in sunshine and able to climb to a more comfortable cruise altitude.

Off and running again, I settled back to enjoy the scenery. I had a small tailwind, and the air was smooth. This was dramatically different from what I had been looking at all morning. The flight to Chandler was 1.9 hours, and I landed in the opposite direction with a nice headwind down the runway.

Chandler has a really nice two-runway airport. I taxied to the fuel pump and was told I was just in time by the attendant, who was leaving sharp at 5:00. While he filled my tanks, I used the facilities, then talked him into letting me lock the airside door on my way out so I could use the pilots lounge to prepare my flight plan for the next leg. He agreed and took off.

I wanted to make it to Minot for the night, but according to my calculations, the furthest I could get before dark was Devil’s Lake, North Dakota. Ironically, I had stopped there when I brought my Starduster home from Nova Scotia five years earlier. So I filed my final flight plan for the day and was off.

My route took me directly over Fargo, ND. There was a lady controller on duty who sounded really friendly. I think she was happy to have me flying through her zone to break up the silence. During the 20 minutes I was on her frequency, the only other traffic was some yahoo using the tower frequency to announce an approach to a small airport about 20 miles away. She straightened him out pretty quick.

This 2.1-hour leg was the best part of the whole trip. The air was smooth, I had a tailwind, and the sun was casting longer and longer shadows across the prairies as I flew on to Devil’s Lake. I felt that fantastic late evening tranquility that only the pilot of a small aircraft knows.

The Devil’s Lake airport is uncontrolled but had an ASOS to give me the conditions. I settled gently onto the runway with a nice headwind about 20 minutes before sunset. I pulled up to the FBO ramp and tied down while there was still some light. Everything was closed up tight, but there was an after-hours number on the door, so I called to let them know I was there and asked for the number of a taxi. Half an hour later, I was checking into a Super 8 feeling great after a beautiful afternoon of flying.

I was at the airport by 8:00 the next morning prepared for a long day of flying. The sky was clear, and the weather reported some light showers about 50 miles west, but only lasting for another 50 miles. I filled up, filed for Williston, ND, and was gone. This 2.2-hour leg would bring yet another metaphysical experience.

It didn’t take long for a low ceiling to develop and some showers to appear. The ceiling was up and down all over the place. For a while, I was down at 400 AGL, then back up to 1500, then down again. Visibility was good, and the prairies are flat, so I wasn’t too concerned. As I was cruising along close to the ground, I studied some of the farms. There were lots of them, and the farmhouses and yards were small and sparse. Suddenly, I was overwhelmed with a feeling I was flying my PA-12 back in 1947 again, looking down at these little farms with old, broken-down equipment in the yards. I fully expected to see a pair of horses pulling a hay wagon. It was neat.

It wasn’t long before the ceiling lifted to a high overcast and everything opened up. I flew past Minot, which I knew well from living there as a teenager. I told Magic City tower I was going by on the south side. The city of Minot calls itself the “Magic City,” so the airport tower goes by this name rather than Minot. There are lots of quirky things like that in the US.

Between Minot and Williston, a strong headwind developed. I tried different altitudes up to 8500 feet hoping to avoid it but was unsuccessful. I could see my day getting longer and longer as the headwind built to 20 mph. Williston was another quick turnaround stop, and I was off on the longest leg of the trip to Havre City, Montana (3.0 hours).

The headwind kept up, and it started to get hot and bumpy. By the time I crossed into Montana, it was really bumpy. Again, I tried different altitudes but found no relief. I was, however, very impressed by the way the PA-12 handled the turbulence. Although it has lots of wing for the bumps to throw around, the ailerons are very effective, and with small stick movements, I was able to keep it reasonably steady.

I landed straight in at Havre among the gusts and hot air rising from the runway. I think I landed three times. Once again, there wasn’t a soul on the airport. I pulled up to the fuel pump and called the phone number listed on the sign (what would I do without a cell phone?). The fuel attendant was somewhere out of town, and it would take him an hour to drive to the airport! I asked him to get there as fast as he could since I had an important date with customs.

I was now in a time crunch. I had intended to clear at Lethbridge, but customs service is not available there after 6:00 pm. So I decided to go into Sweetgrass, on the border. The last time I was there, the runway was terrible, so I was a little concerned this time. As it turned out, the PA-12 handled it just fine.

I was getting anxious sitting on the hot ramp trying to estimate when I would be able to take off. I had to give Canada customs 2 hours’ notice before arriving in Sweetgrass, but it was only a 1.2-hour flight. I figured the attendant would take 15 minutes longer than he said and estimated my time off from that. I called customs and booked an arrival time, then filed a flight plan, and waited some more. He actually arrived on time, and I was able to get away within a few minutes of my estimate. Sometimes things work out.

The leg to Sweetgrass was as rough as the previous one. But I arrived within 5 minutes of estimated time. On final, I saw the customs agent sitting in his car waiting for me – about 20 feet from the end of the runway. I flew directly over him and did a nice landing on the grass strip, turned around, and taxied back to where he was waiting. He just glanced into the airplane, then told me to grab my paperwork and we would drive to the customs building at the border crossing. Once there, all he wanted to see was the bill of sale so he could collect the GST. Once I paid that, he drove me back to the airplane and wished me a good flight. Nothing to it, as long as I had enough room on my credit card.

Finally, I was on the last leg home. Two more hours and I would be at Chestermere Kirkby Field. Away I went, this time without being able to fill up. However, by now I had a good handle on my fuel burn, and the total time for these two legs would be 3.4 hours out of a total endurance of 6 hours.

Halfway between Lethbridge and Vulcan, I heard a familiar voice on 126.7. Gary Able was broadcasting a position report as he passed Claresholm on his way home to Chestermere. I called him, and we chatted for a little while.

Finally, I had home base in sight. I crossed mid-field and joined the downwind for 34. After twelve hours of some grueling flying, I was tired and wanted to get on the ground and have some dinner. I came in too hot and forced the PA-12 to land sooner than it wanted to. The result was three landings, but it finally stopped before I ran out of runway. I taxied in to find Brian Vasseur and Ed D’Antoni chuckling over something… can’t imagine what.

I was, however, glad they were there to help me push the aircraft into the hangar in my weakened state. It was finally parked in its new hangar after a trip of 1760 miles in 19.2 hours. An average of 92 mph. Not bad considering half the trip was against very strong headwinds with an airspeed of between 100 and 105 mph.

Having completed the authorized ferry flight, my PA-12 was now grounded until I finished the importing process and obtained a Canadian C of A, which would take six months. But that’s another story.