What would you do if you didn’t have to work for a living? I’m sure most of us have asked ourselves that question. Sometimes the question is rephrased as “What do you want to be when you grow up?” As a child, we have more time to dream than perhaps we do as adults. And with each tomorrow, we had more time to dream the impossible. But as the years passed, the list of unfulfilled dreams became ever longer.

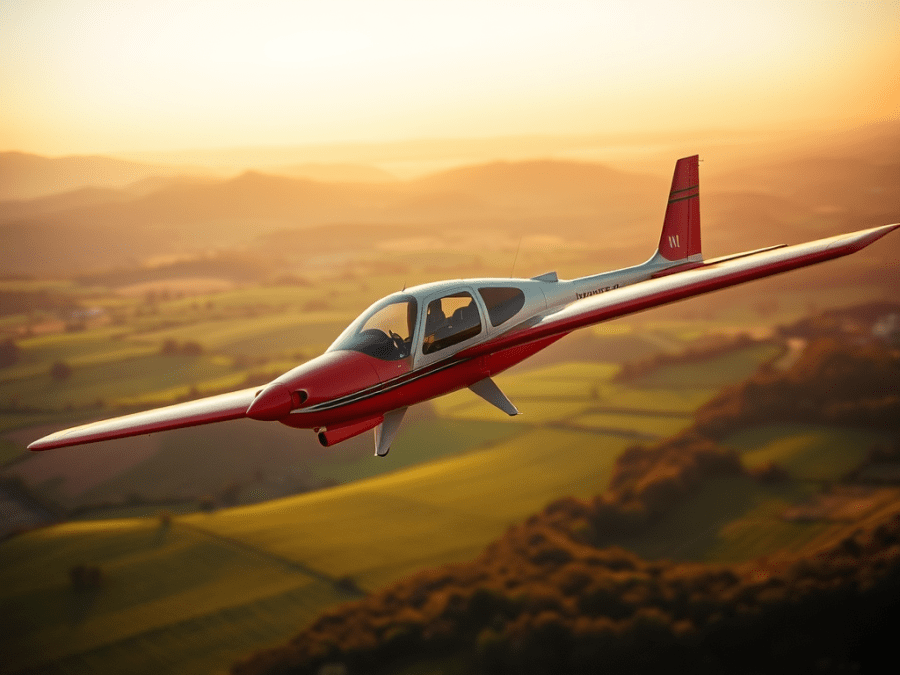

When I was young, I dreamed of being an astronaut. In the era of man walking on the moon, what boy didn’t want to be one? Later, it was enough just to be a fighter pilot. From the first time I watched “Top Gun” to today, I still get that desire to strap myself into a fire-breathing bird and rocket through the air. I twice considered pursuing that dream but was led to disappointment by the reality of too many people pursuing so few positions as military fighter pilots. And in my case, with a challenging engineering future ahead of me, my mind was focused on staying the course.

Throughout university, not only did I dream of flying but I also dreamed of designing and building airplanes. At first, this seemed a little far out there, but as time went on, I began to believe that this dream was, in fact, one that could actually turn into reality. All it would take was money and time. Yet after graduation, the difficulty in accumulating enough money and time for flying became very apparent.

Why is it that a car loan often accompanies that new set of wheels in the driveway? And why does a mortgage come hand-in-hand with that nice house we live in? Well, whatever the reason, buying an airplane becomes a lower priority when trying to pay down debt. And buying a kit plane that will take years to build is even lower on the priority list. So why do we bother to even dream about such things? Well, if you’re a pilot, you already know the answer. Few things are closer to the heart of a pilot than to fly.

After receiving my private pilot’s license a few years out of university, I began renting airplanes as most new pilots do. But as time became more valuable, with the ongoing competition with student pilots to rent airplanes at local flying clubs when the weather was VFR, it became more difficult to regularly enjoy the freedom of flight. Sometime after moving to Calgary, I became involved in the Calgary Ultralight Flying Club (CUFC). Much to my surprise, I learned that owning an airplane was actually something I could afford. Not only that, but I could also actually build one! Many other members in the club had already done that, so why couldn’t I? Hmm, now what would I really like to build?

Perhaps the first factor I considered was the seating. Previously, I’d taken a number of people flying as most new pilots do. However, in the times I flew alone, I always wished for better visibility to view the land and sky around me. Most rental planes have side-by-side seating with limited visibility out the right side. However, tandem seat airplanes solve the visibility problem, albeit with other drawbacks such as a smaller instrument panel and a less sociable setting. But with an intercom, communication with a passenger shouldn’t be too significant.

Looking at structure, I preferred to build a plane with a strong aluminum frame. Fabric covering offered a lower cost, more forgiving, and lower construction time alternative to metal skin. Given the abundance of ultralight planes with Rotax 503 engines, I was satisfied that this was a higher value, lower risk option than many other available engines.

When I finally considered the history and general acceptance of the design, I ended up choosing to build a Challenger II. At the time, there were some 3000 Challengers flying globally and 400 registered here in Canada. Not surprisingly, there were several flying in the Calgary area. When I finally wrote the cheque for the kit, I learned that another local builder was also early in the process of building a Challenger II. Throughout the project, Robin Orsulak and I helped each other out and edged each other on. The “Challenger Junkyard Wars” lasted about four years until two new Challengers took to the skies.

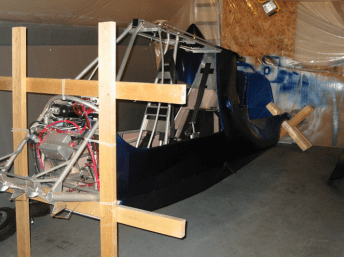

The day the kit arrived was one of great satisfaction. Like the times we head out on big adventures, the excitement of the fun times to come was difficult to contain. The Challenger kits come with the tubular fuselage structure essentially built. So, it didn’t take much effort to visualize an airplane from the skeleton of metal. In fact, I was able to put a cushion on the pilot’s seat, climb into position, and take a few minutes to dream of the future flights this plane would take me on.

Beginning with the tailplane, it was relatively easy to learn the basic metal skills of drilling, deburring, rigging, and riveting, as well as the basic fabric skills of fitting, gluing, heat-shrinking, and sealing. And so it did not seem to take long before six pieces of the plane were ready for priming and painting. I was satisfied with my progress, but little did I know then about all the obstacles that I would face along the way.

With the tailplane out of the way, I began constructing the wings. The spar structure of the wings was assembled at the factory, and I took over with the installation of ribs. Perhaps it was at this time that I really began to understand that putting together a kit plane was considerably more difficult than building a RC model plane. I recall many times measuring more than twice before drilling once. And despite the acceptable results, perfection seemed ever more unattainable. Eventually, fabric covered the wings, and once again I felt satisfaction with my project. But there was a winter that I did little on the plane as I needed warm weather to complete the fabric work (due to my unheated, unventilated garage workshop).

Not long into the project, I began designing the instrument panel. With the help of software and a plotter, I was able to make dozens of revisions and sequentially print each one (full-size) and position it on my airplane. When the day finally came to fabricate the panel, I sent an AutoCAD file to a local Calgary shop that cut the panel out of aluminum with a computer-controlled water jet. The result was awesome. After a short visit to another shop to bend a structural lip along the bottom, I was ready to begin installing the gauges that I had been purchasing over the previous year(s). And although I had visualized the results many times, to actually see and touch it gave me a feeling of satisfaction and pride. I recall bringing my semi-complete panel to a local club flying event to show it off like a baby.

The wiring came next and seemed to last for the duration of the project. When I first thought I was 90% done, I may yet have had another 90% to go. With each new wire that was added, the bundles had to be tie-wrapped again so that everything was just right. And the wiring of the instrument panel was perhaps more of a work of art than function. Oh well, that kept me doing something during a cold winter (or two).

When the warm weather of spring finally arrived, I was able to begin priming and painting my plane. I really wanted a metallic look to my plane and consequently shied away from using Poly-Tone, even though I used Poly-Brush to seal the fabric and Poly-Spray for primer. I ended up choosing a two-part Endura for paint (plus flex agent) for a nicer finish but may have reconsidered that decision had I known the degree of difficulty associated with applying it. I was able to borrow an HVLP paint sprayer from fellow CUFC member, Carl Forman, to whom I am grateful. It made the process of priming and painting a little more enjoyable or a little less annoying depending on whether the glass is half full or half empty. But in hindsight, it probably would have been better for me to take all the parts to a paint shop and get them painted quickly and professionally. With each project, we learn things about ourselves, what we like to do and what we don’t. Note to self for the next project.

In time, the plane parts were moved to a hangar, and final assembly began. But as straightforward as the process seemed, the devil is in the details and the process took months. Still, in July of 2005, my plane passed the final inspection. Registration took another month even though all of the paperwork was in order, and it was dropped off at the local Transport Canada office.

During the time I was waiting for the Certificate of Registration, I began the engine testing. The Rotax manual provides a detailed procedure for the first hour of operation. Robin Orsulak was there to help me, and it went well. However, I seemed to have spent a few hours tinkering with the idle trying to get it just right. In the end, I settled for a higher idle speed that gave a much smoother running engine. Interestingly, as I worked through perhaps the first ten hours of engine operation, the sound and performance seemed to improve to the level experienced by other owners.

Finally, in October of 2005, my Challenger took to the sky with the aid of Robin as my co-pilot. After an interesting lift-off, I rapidly became aware of the flying characteristics and was able to fly more confidently. After two or three circuits of dual, I took the plane up solo and had my first real lesson on the performance difference of a lightly loaded Challenger II versus one closer to gross weight. If the Cessna 172’s I previously piloted were considered docile, the Challenger II was sensitive. On the ground, I adjusted the elevators and ailerons to get a near vertical stick in straight and level flight. And after enough flights, I became very comfortable in this agile airplane.

Eventually, I began taking people up for rides in my plane to show them what I’ve been working on all this time. While many people from work had previously joked about my kit plane project, a growing number of them seem to get caught up in the excitement and awe of it all. However, there will always be some who can’t understand why I would build a plane to fly around the countryside to enjoy the camaraderie of fellow builders and pilots. Perhaps they are typical of those that will only walk on the earth while we pilots soar through the heavens.